Every family has a ‘fruitcake’, this post is about ours!

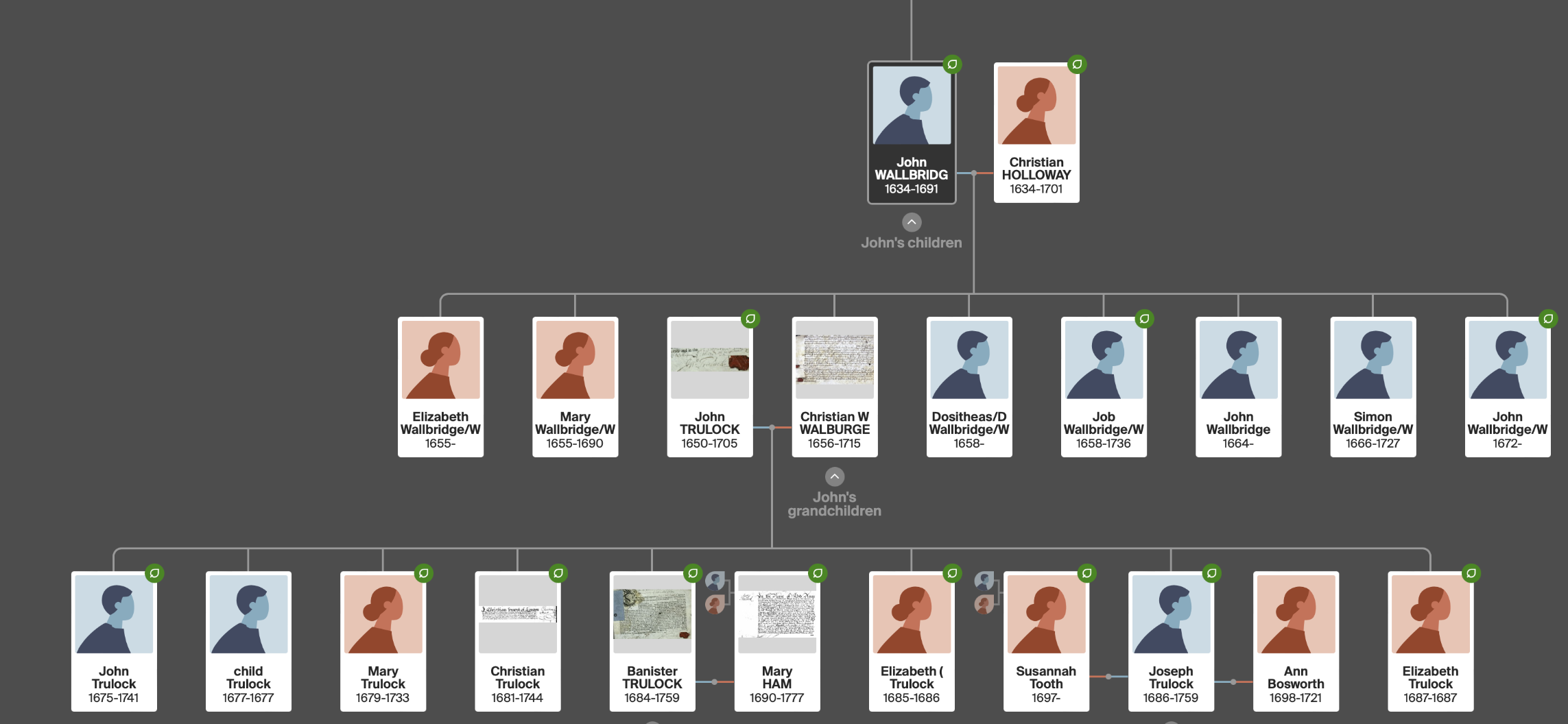

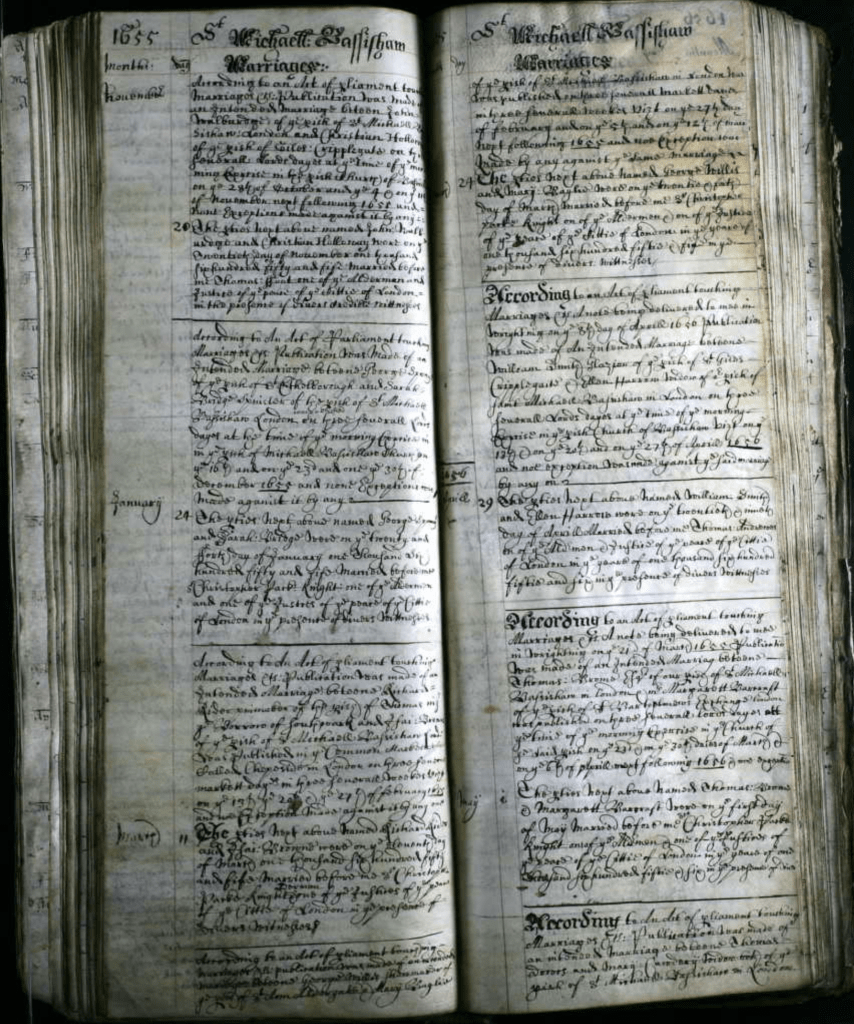

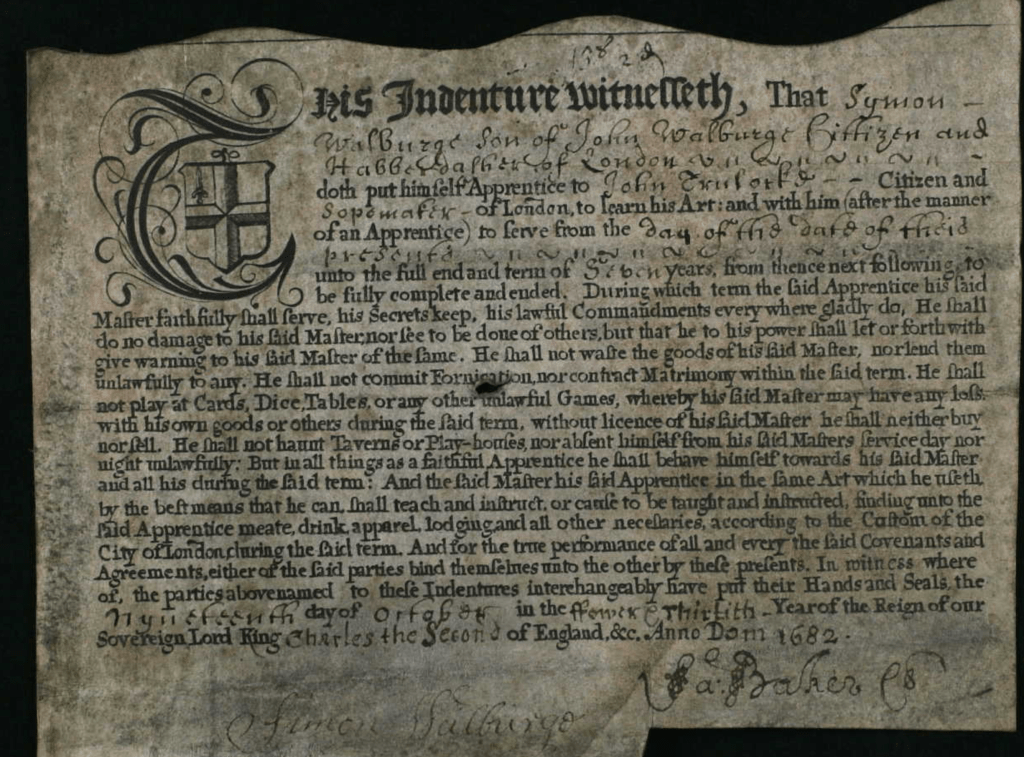

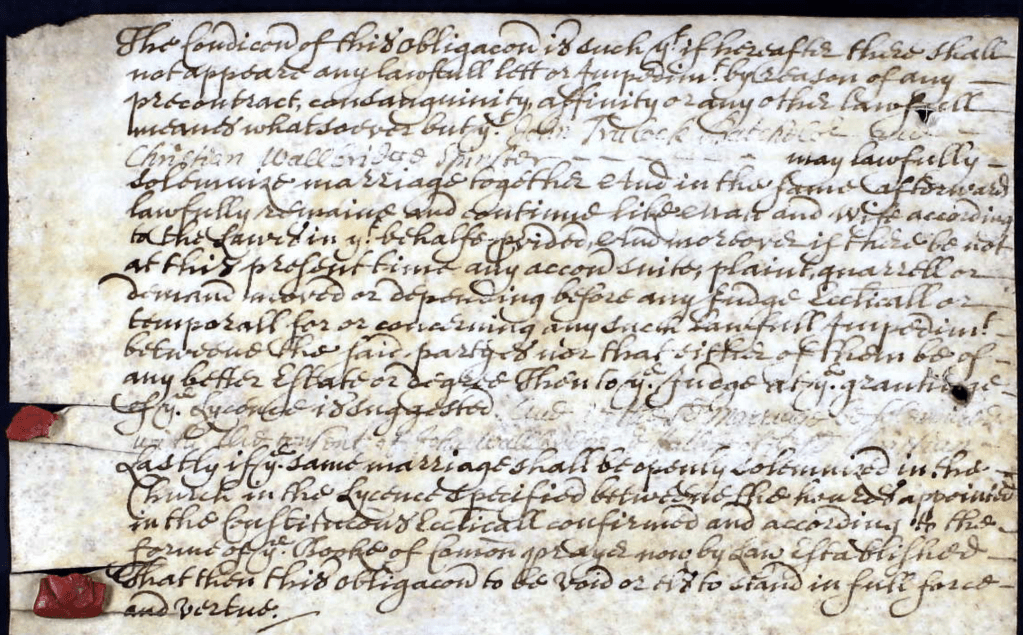

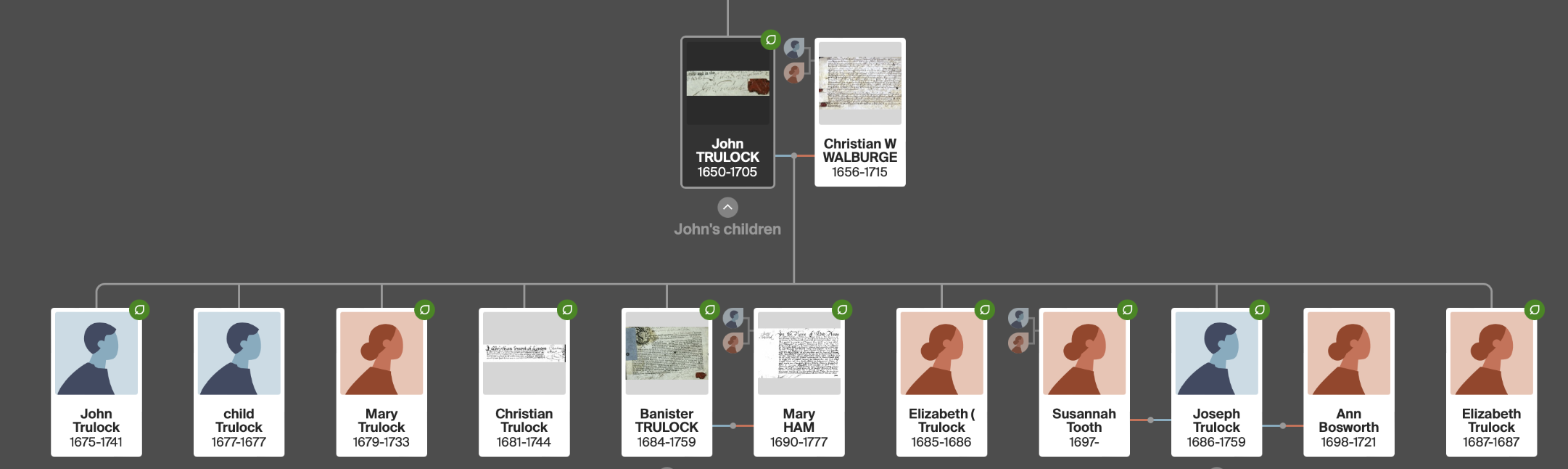

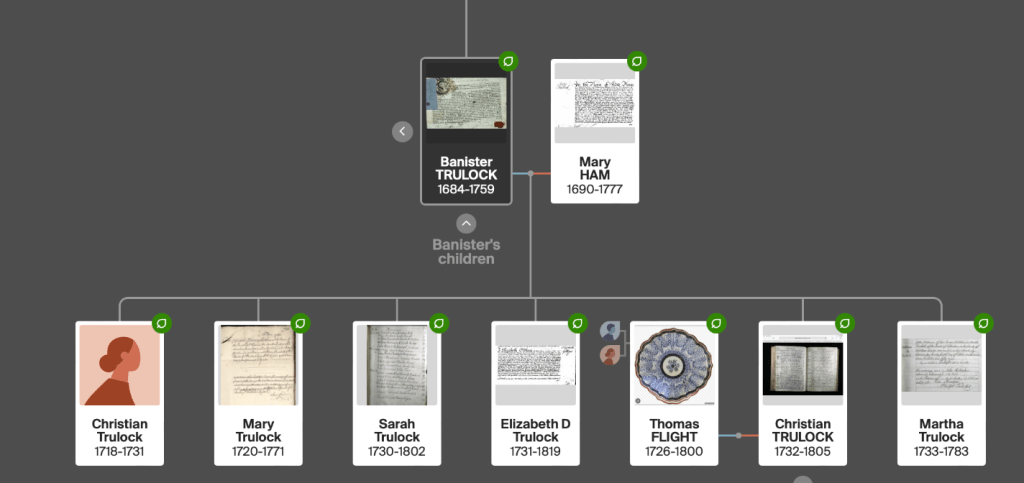

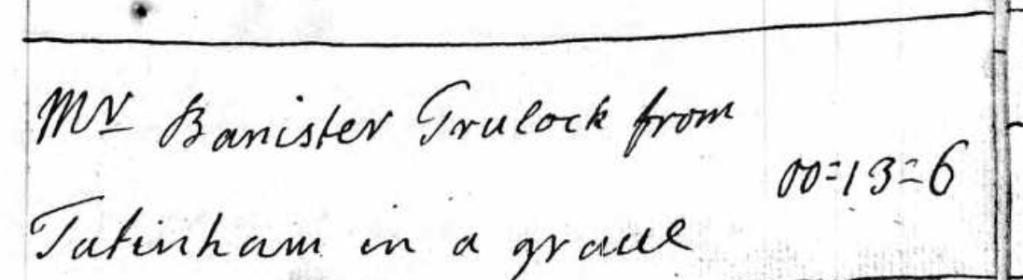

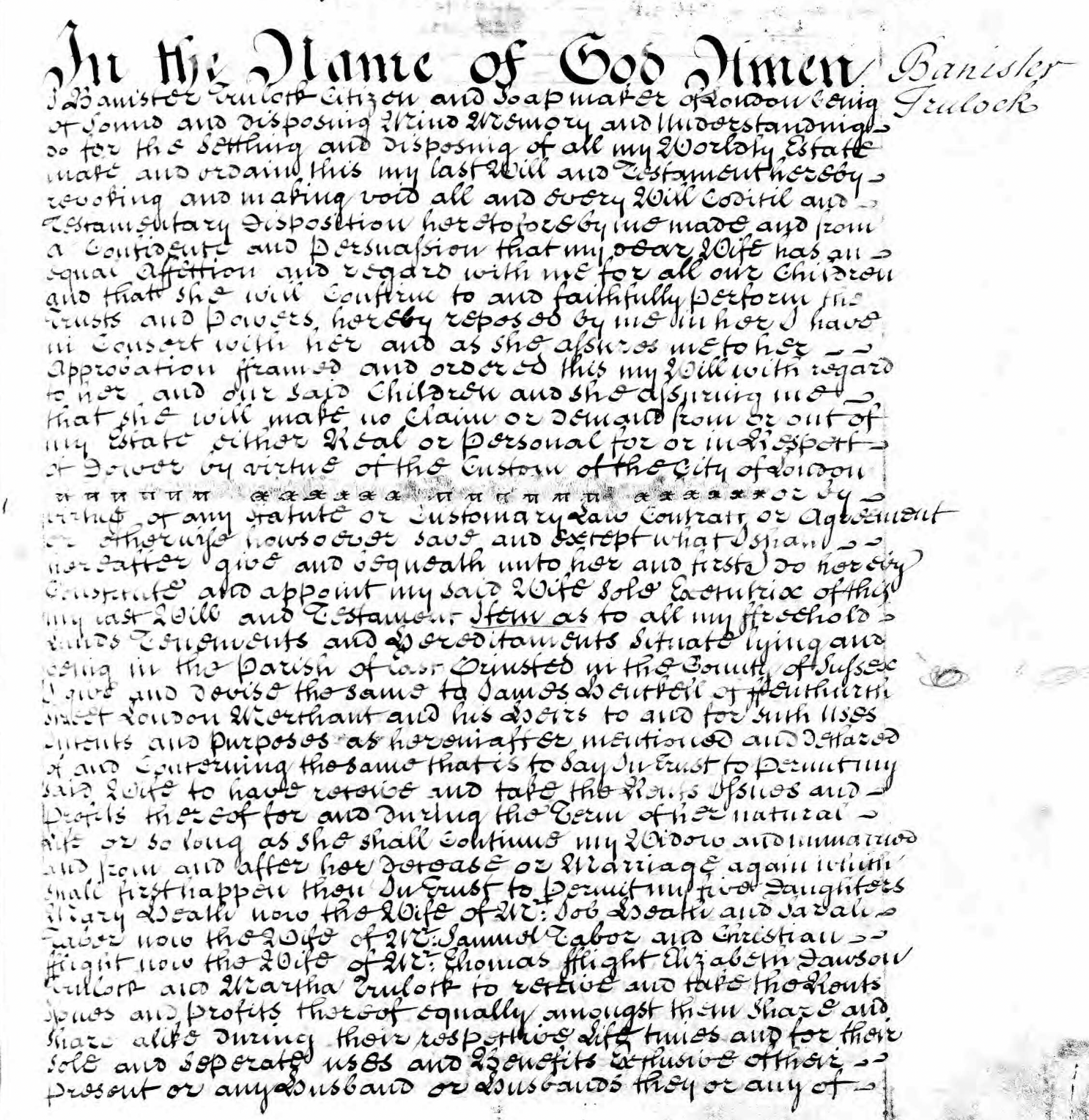

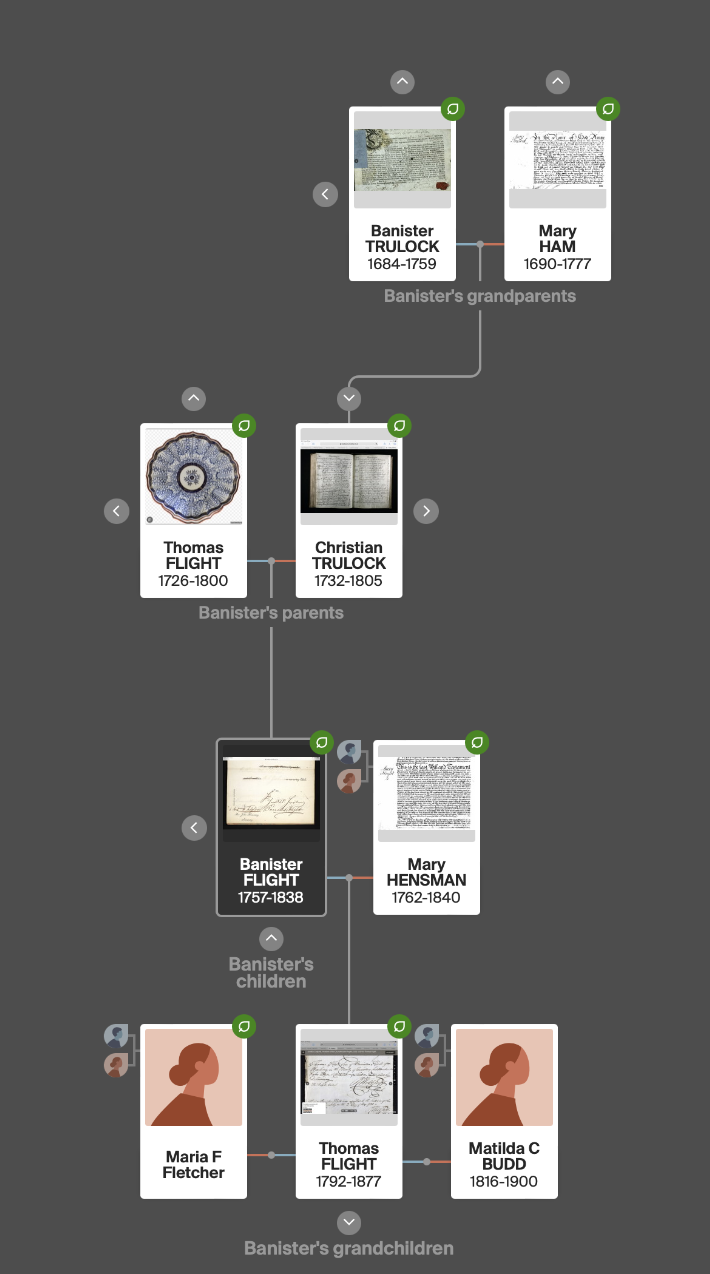

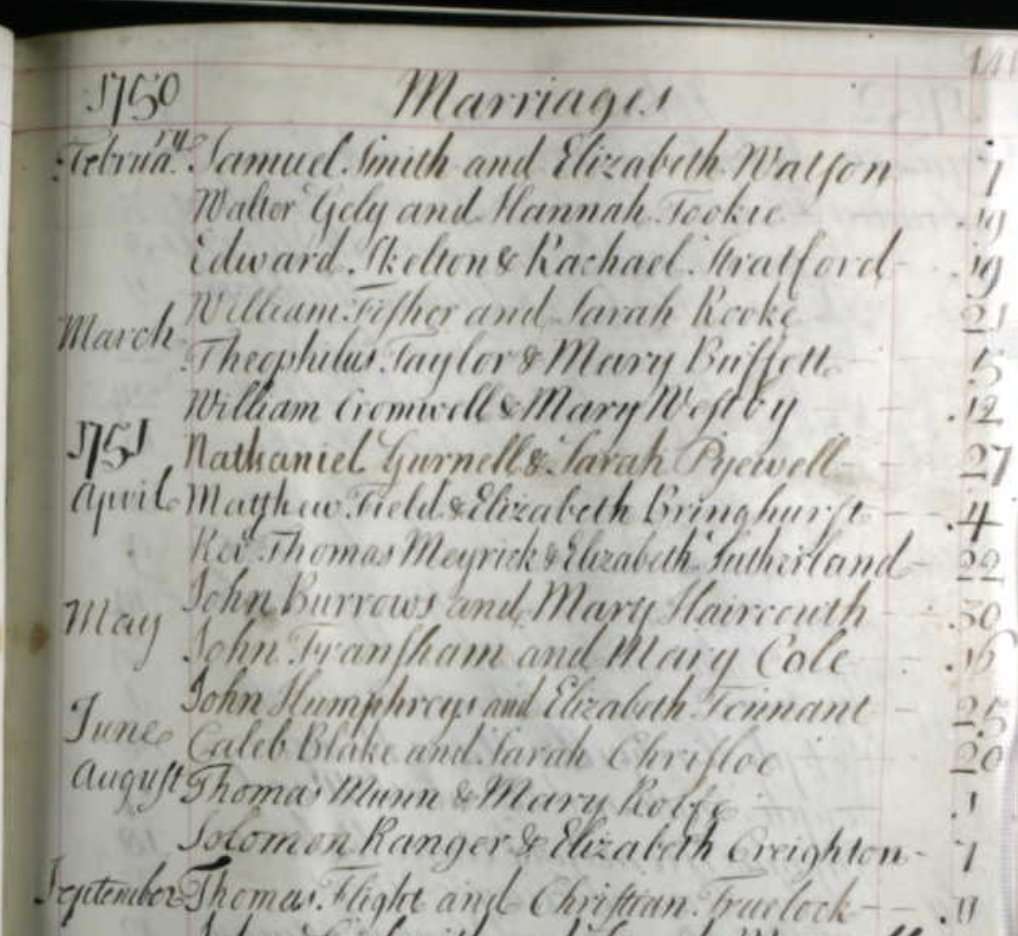

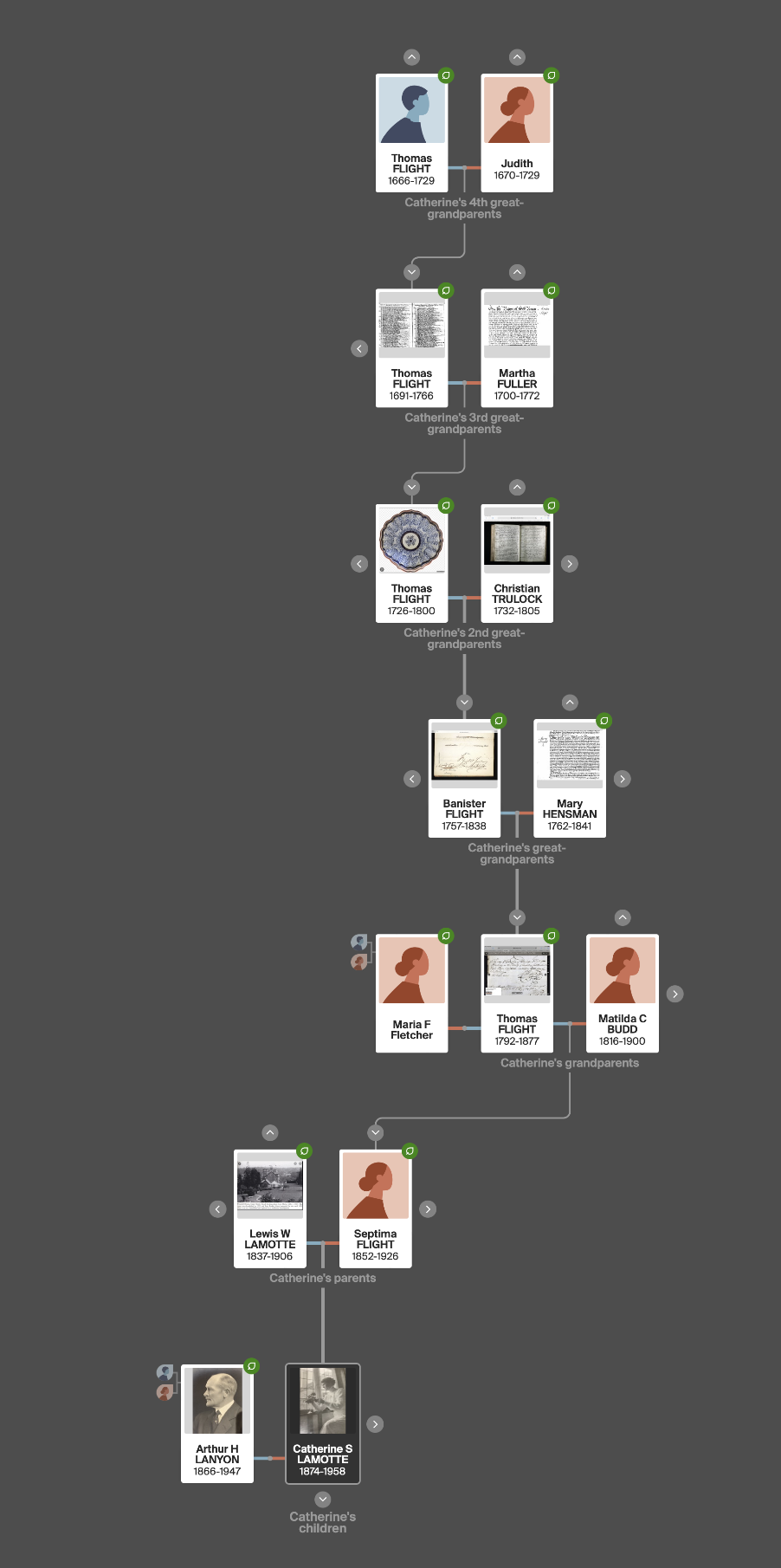

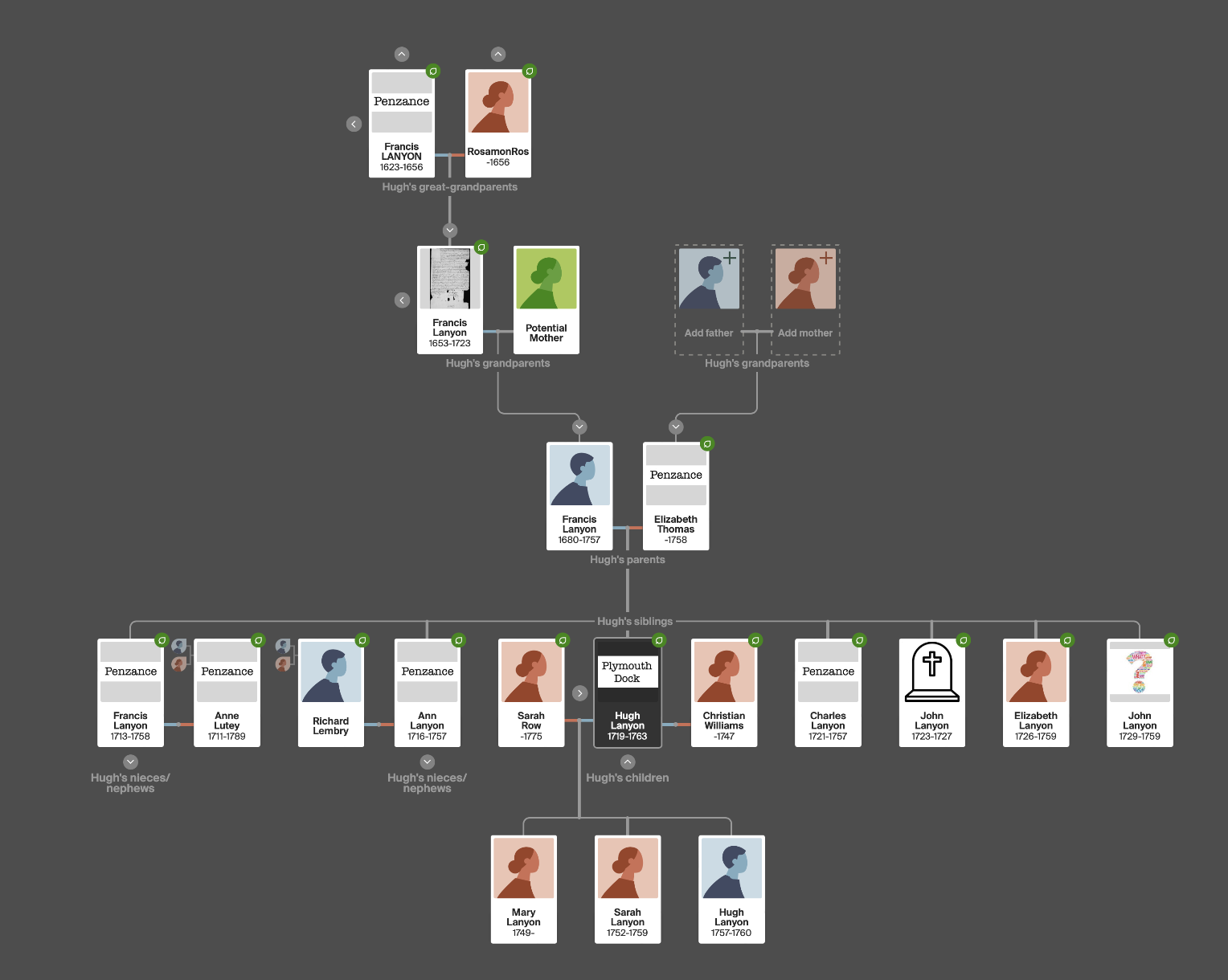

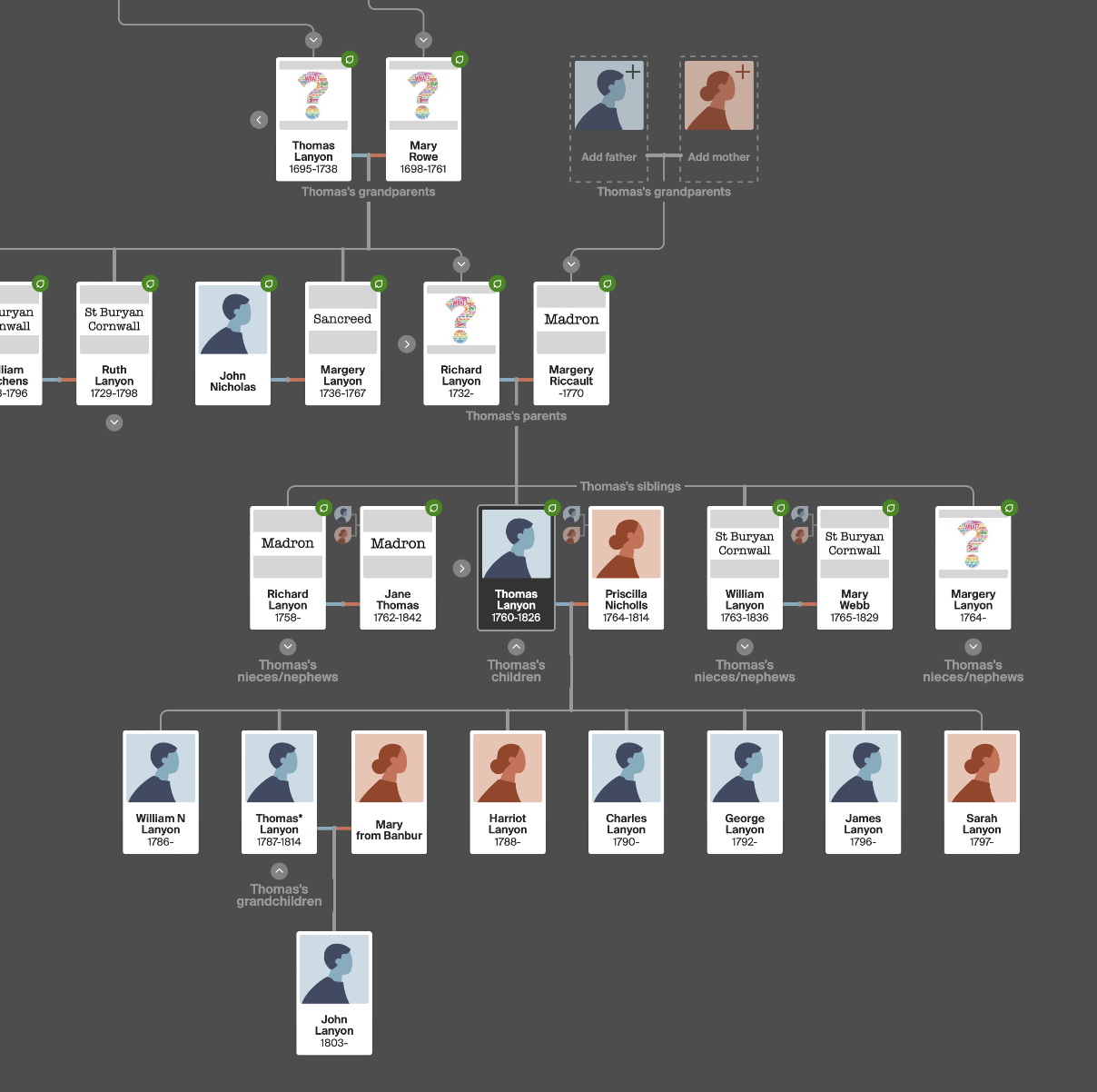

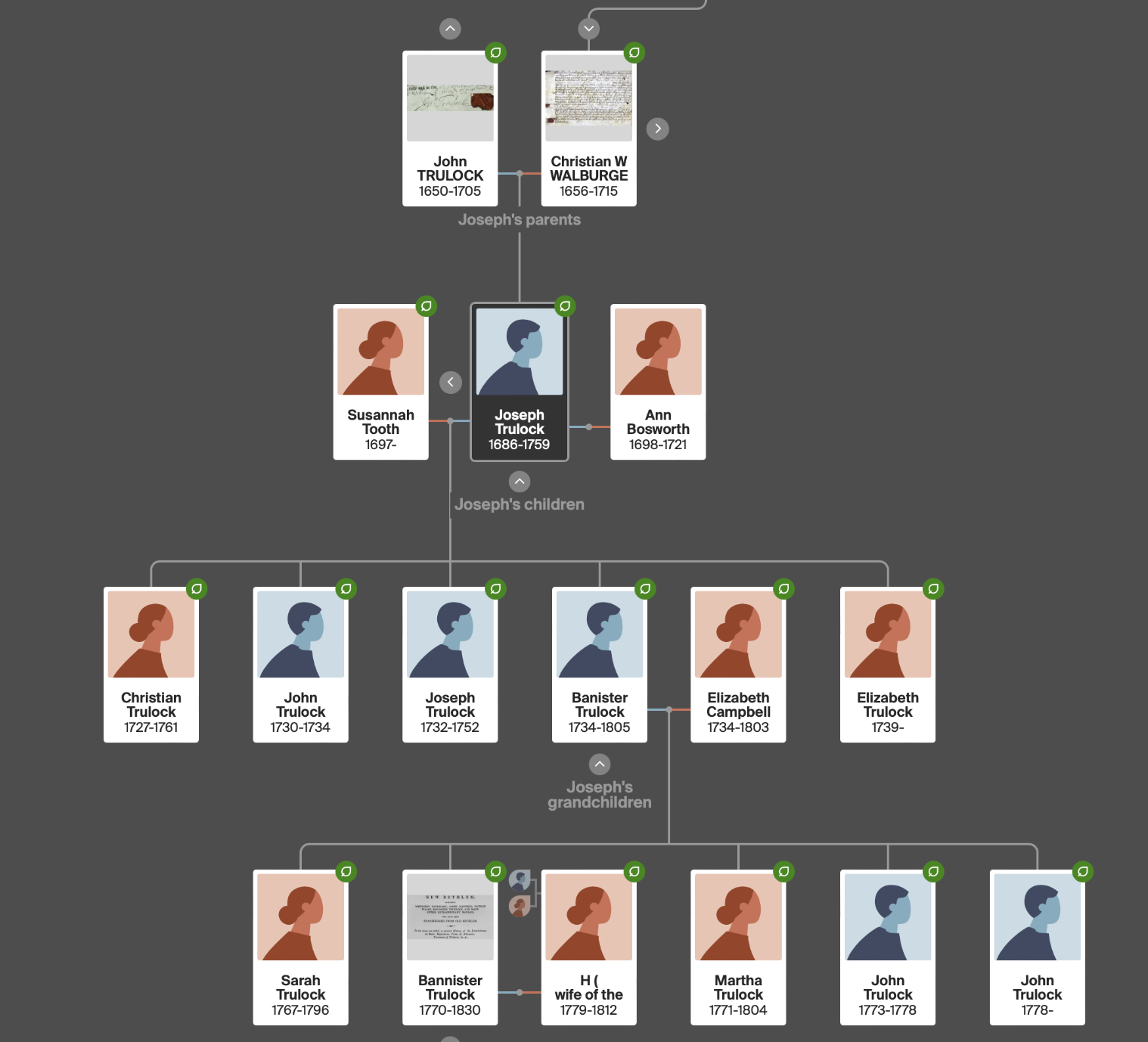

John Trulock and Christian Wallburge were the great grandparents of Banister Trulock born in 1770.

Their son Joseph Trulock married Ann Bosworth on 25 Feb 1719 at St Benet Paul’s Wharf, London. Ann sadly died in Sep 1721 and Joseph remarried on 07 Jun 1722 • St. Anne’s Church, Lewes, Sussex to Susannah Tooth.

Their first two sons John and Joseph died young and that left their third son, Banister as the eldest son and heir.

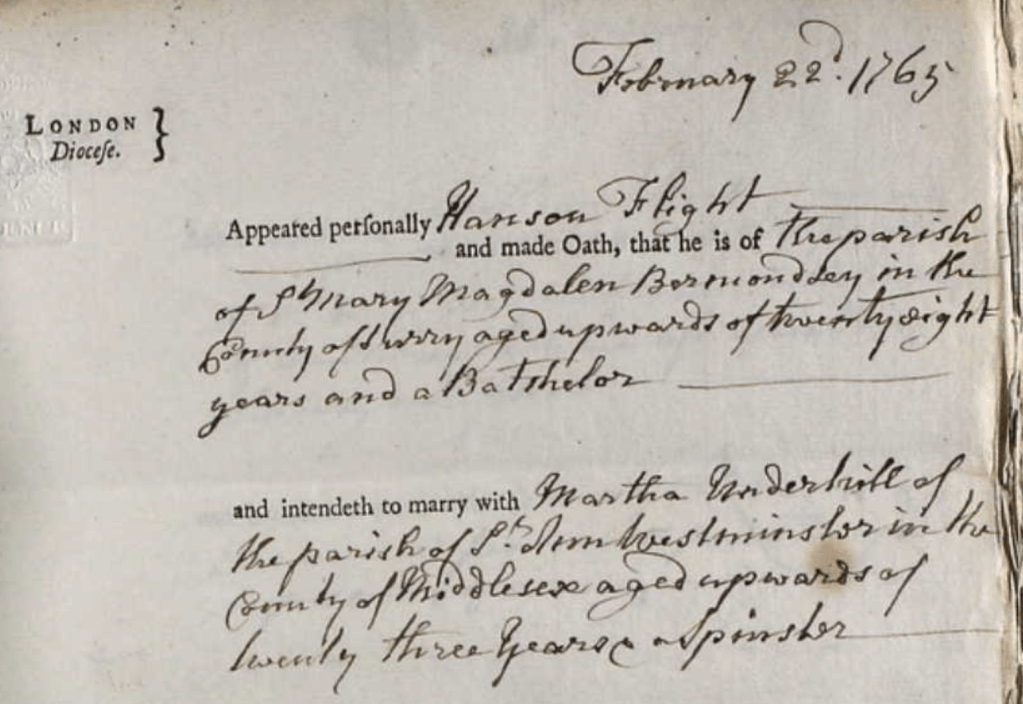

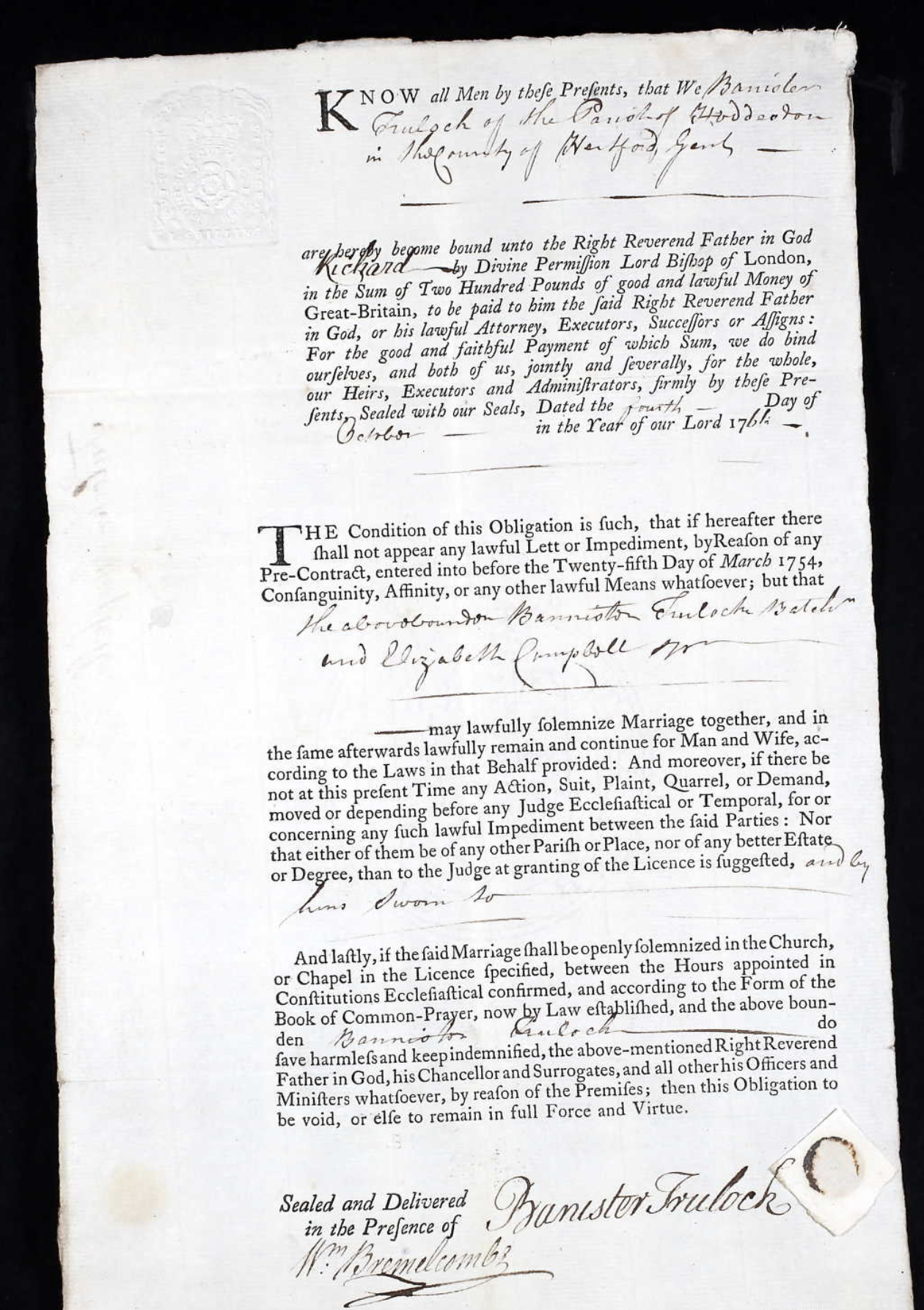

Banister was born about 1734 in East Grinstead. He married Elizabeth Campbell 05 Oct 1766 at Broxbourne, Hertfordshire. He signed a marriage bond.

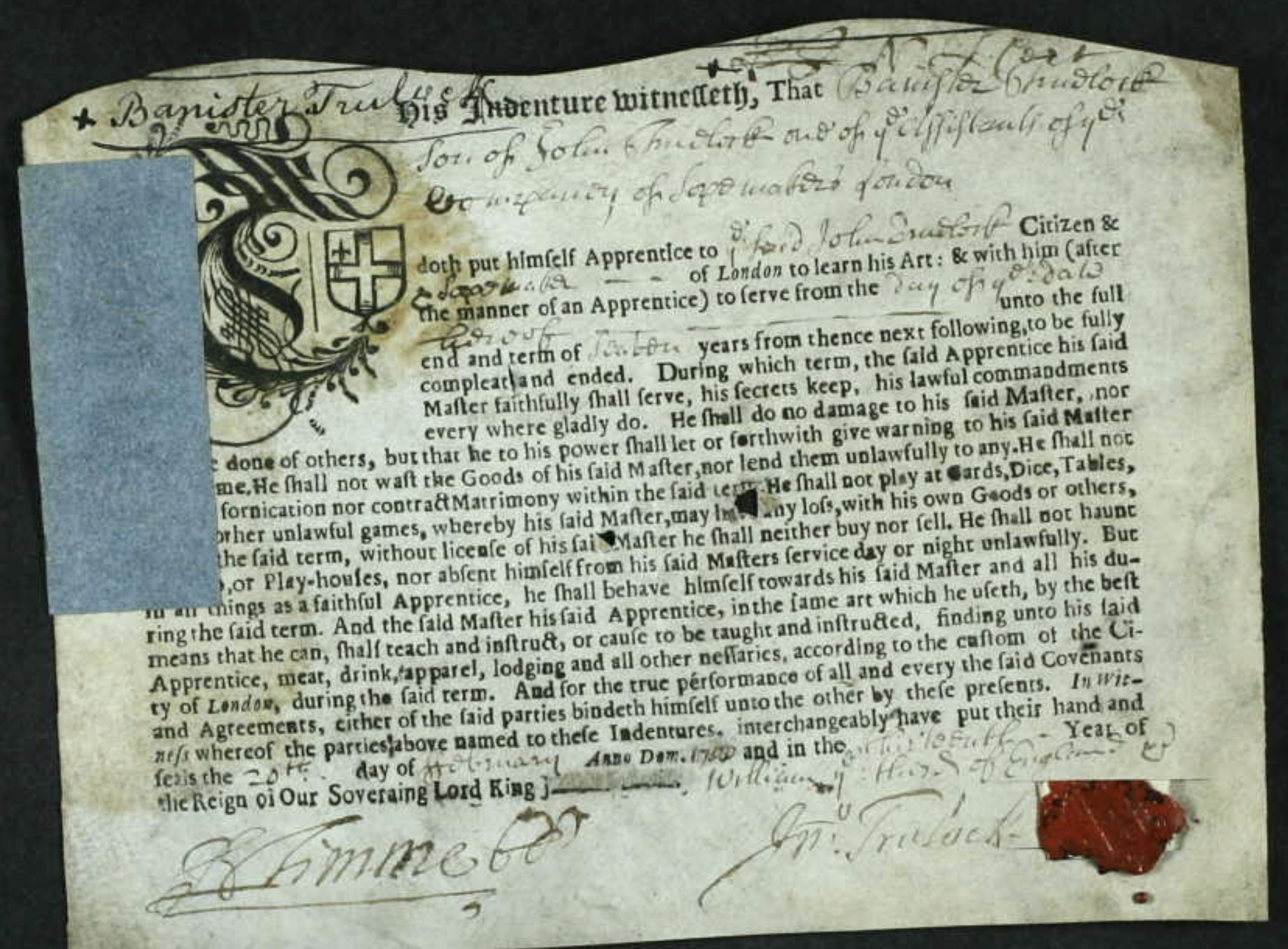

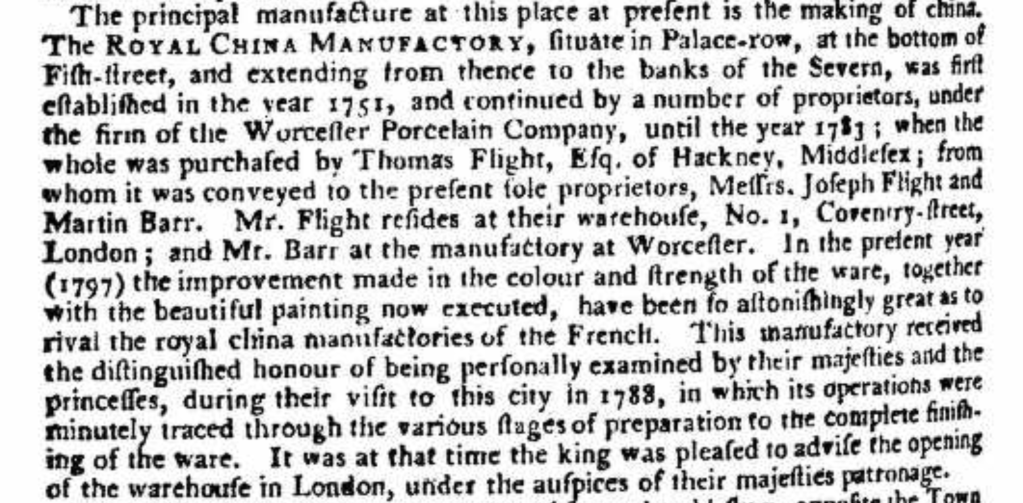

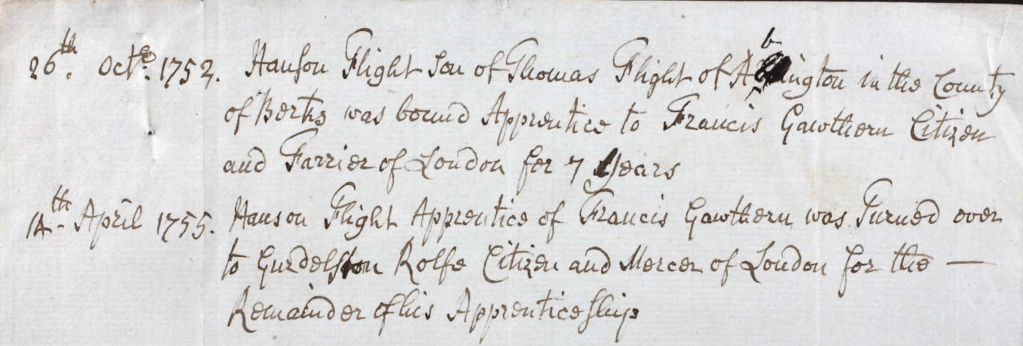

Their son also called Banister was born about 1770 at Hertfordshire. In 1783 Banister was apprenticed to John Payne a cordwainer in East Grinstead, Sussex. His father is described as a husbandman.

(The name Banister and Trulock are variously recorded as Bannister, Banester and Truelock.)

Before 1799 he married Ann/Hannah and they had two sons: Banester who died age 4 and William Henry who was baptised in 1812.

Banister was a religious fanatic who prophesied the second coming of the messiah. He also insisted in the belief that the Messiah would be born from his mouth!

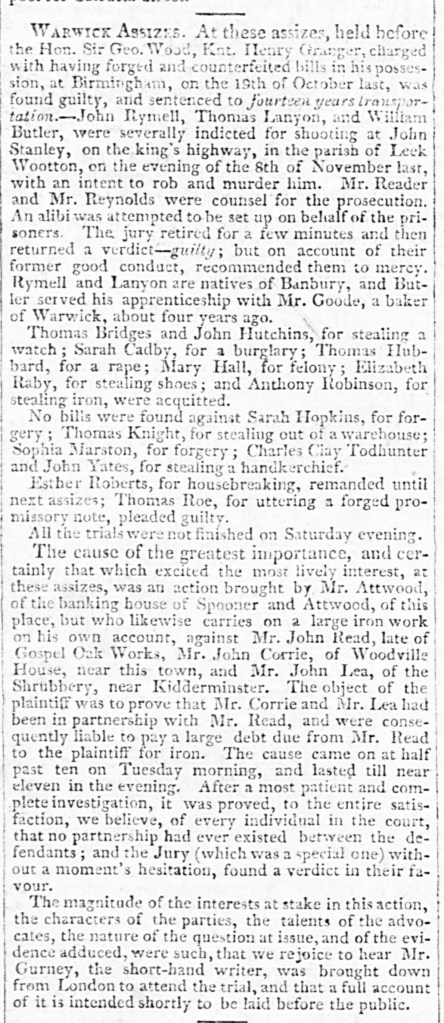

“He met Hadfield by accident in White-Conduit Fields, and talked the unfortunate fellow into a persuasion, that the first step to the commencement of his doctrines, and to its fulfilment in a happy change of things throughout the world, would be the death of the Sovereign ; with this view, Hadfield set out as the supposed chosen instrument for the accomplishment of the great design. Hadfield, in his examination, mentioned this man’s name ; he was accordingly apprehended the next day, underwent several examinations, and was committed to prison ; but from his incoherent manner, his answers, and the evidence of his mother, he was found to be deranged, and was sent ultimately to Old Bethlem.By May 1800 he was working as a shoemaker and living in the White Lion, Islington, London. Whilst there he was visited by James Hadfield, whom Trulock encouraged to try to assassinate King George III. ”

Source – https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males

He was lodging with Sarah Lock until Dec 1799, she evicted him after he told her on Christmas Eve that there was a plot to assassinate the king. (Source: Hampshire Chronicle, 2 Jun 1800)

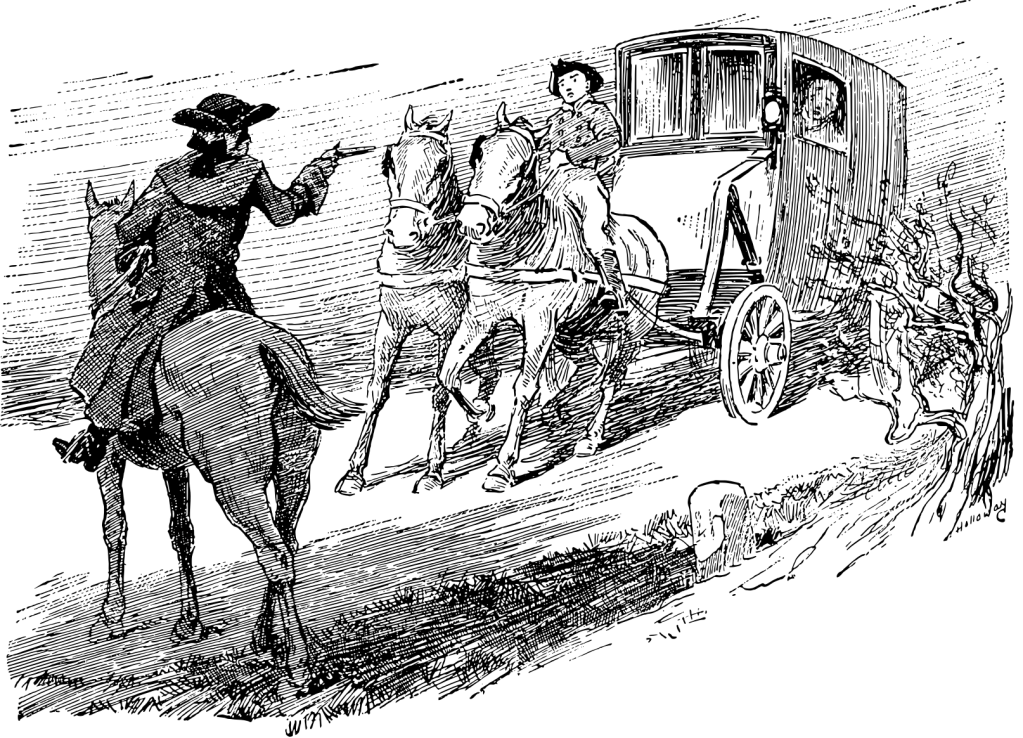

The Assassination Attempt

At the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on 15 May 1800, James Hadfield tried to shoot King George III while the national anthem was being played, and the king was standing to attention in the royal box.

It’s reported that after missing his target, Hadfield then said to the king:

‘God bless your royal highness; I like you very well; you are a good fellow.’

Hmm, we’re thinking that his words might be a very good examples of quick thinking…

Hadfield went on trial for high treason but, after listening to evidence from three doctors as to Hadfield’s state of mind, the judge decided on an acquittal, with the proviso that Hadfield would be detained indefinitely at his majesty’s pleasure.

Hadfield died from tuberculosis in Bethlehem Hospital (i.e. ‘Bedlam’) in 1841.

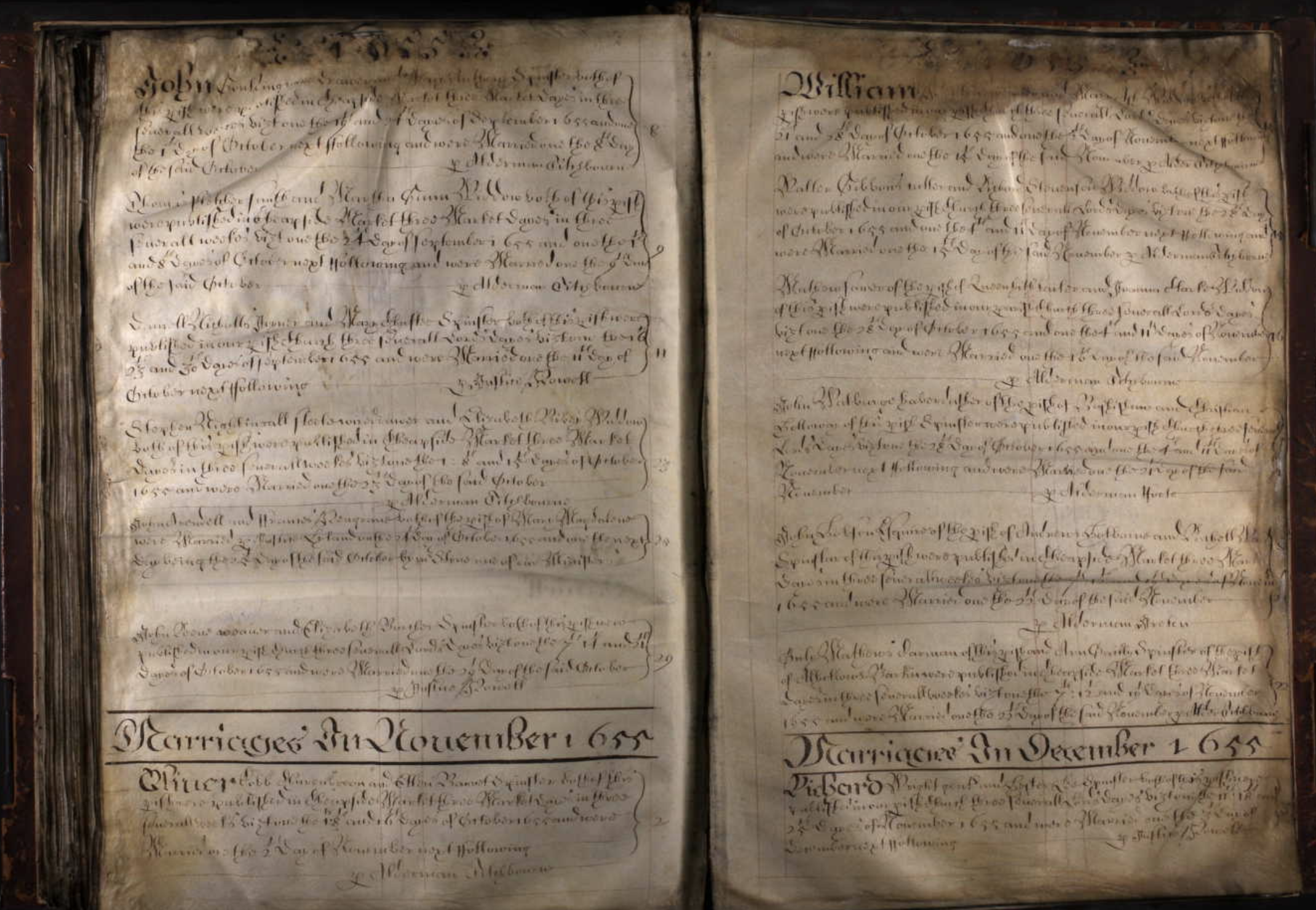

Chester Chronicle – Friday 27 June 1800

Banister Trulock was apprehended the next day and was committed to prison ; but from his manner, his answers, and the evidence of his mother, he was found to be deranged, and was sent to Old Bethlem.

Visitors reported that he sounded sane until he started to discuss religion. He was kept in some comfort and had an apartment at the top of the hospital which had a view of the Surrey hills. He had ‘coal, candle and every convenience for his use; his provisions are regularly brought to him and in the fine weather he is permitted to walk in the garden.’

He was later moved to New Bethlem hospital.

Visitors to Bethlem could pay to ‘view’ the patients and Banister Trulock was one of the celebrated patients.

Banister died on 02 Nov 1830 at Bethlehem Hospital, St Saviour Southwark, London