Settlement Certificates or Paupers Passports were documents that in effect permitted poor people to travel between parishes usually to look for work.

Under the old Poor Law everyone was deemed to have a home parish or place of settlement. The Act for the Better Relief of the Poor of 1662 (Act of Settlement) was an attempt to provide for the poorest, to prevent migration and to restrict the arrival of vagrants who may become an expense for the parish.

In effect it tied labourers to a particular parish and enabled employers to exploit them and pay poor wages as they could not leave to search for work elsewhere.

Eventually Settlement Certificates were issued. These documents proved an individual’s parish of settlement, enabling him or her to move to other parishes, perhaps to find work. Without one, a migrant was liable to be sent back to his or her parish of settlement. Settlement certificates could be issued for individuals or whole families. They guaranteed that their home parish would pay for their ‘removal’ costs (from the host parish) back to their home if they needed poor relief.

If a removal order was issued the Settlement Certificate would be pinned to the pauper and they would be returned to their home parish.

In 1834 the New Poor Law was brought in and ensured that paupers were clothed, housed and fed but many still encountered terrible problems when they fell on hard times.

This post is about Louisa Lanyon and the order to remove her and her child from St Allen to Mawgan in Meneage in 1856.

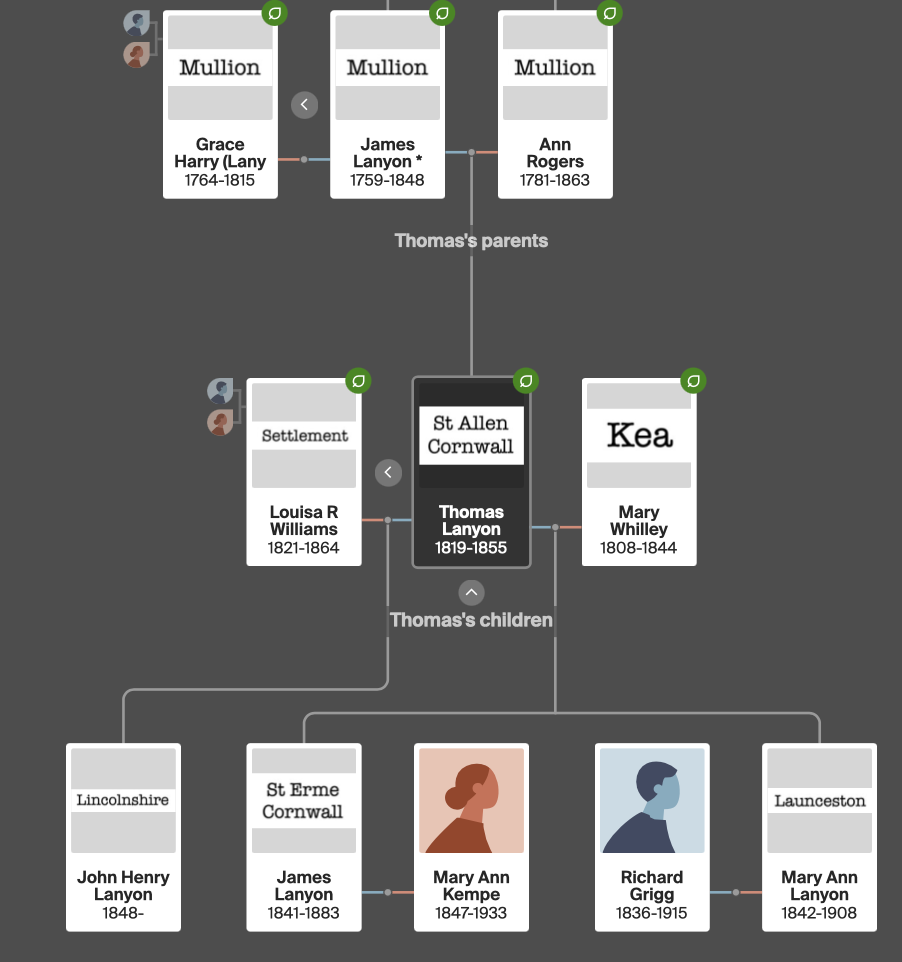

Louisa was the wife of Thomas Lanyon. She was baptised on 22 Apr 1821 at Kenwyn in Cornwall, the daughter of Soloman and Ann Williams. Thomas was the son of James Lanyon and Ann Rogers and was baptised in 1819 in Mawgan in Meneage. James, a widower, got Ann Rogers pregnant and had to marry her. He became a father again at the age of 60!

Thomas married his first wife Mary Whilley abt. 1840 and they had two children, James and Mary Ann. Mary died in 1844 and Thomas married for a second time in 1845 to Louisa Rawling Williams at St Allen.

Thomas was a labourer/husbandman and he died of kidney disease on 4 Nov 1855 at St Allen aged just 36. Louisa was left a widow with a young son, John Henry Lanyon and James and Mary Ann were left orphans.

The Parish of St Allen, full of compassion for the young widow and her son, promptly ordered her removal back to Mawgan in Meneage, her husband’s home parish (wives automatically assumed the home parish of their husband on marriage) even though Louisa had never lived there or knew anyone there.

Louisa appealed:

Removal Order Appeal – 9 April* 1856 – Louisa Lanyon, widow, and son St. Allen to Mawgan in Meneage

MAWGAN IN MENEAGE, appellant; Mr. Shilson and Mr. F.V. Hill. ST. ALLEN, respondent; Mr. Childs and Mr. Chilcott.—An appeal against an order by H.P. Andrew, Esq., and W.P. Kempe, Esq., for removal of Louisa Lanyon, widow, and John Henry, her son, aged 7 years, from the parish of St. Allen, to Mawgan in Meneage.

Settlement in respondent parish being admitted, the appellant set up a settlement of pauper’s deceased husband in the parish of Cury, by hiring and service with Mr. James Randle, farmer, of Colvenor in that parish.

Mr. CHILDS took a preliminary objection to the ground of appeal in which it was alleged that, ‘in or about the year 1831,’ the pauper’s husband, Thomas Lanyon, hired himself to James Randle of Cury,—the objection being that the words ‘in or about the year 1831’ were not sufficiently definite to establish a complete year’s service prior to the year 1834—the date of the Poor Law Act, which abolished settlement by hiring and service. In support of the objection Mr. Childs cited the cases of St. Ann’s Westminster, and St. Paul’s Covent Garden.

The Court overruled the objection, and held that the grounds of appeal would enable the appellant to go on.

Mr. SHILSON then stated the nature of the appellant’s case—for establishing a settlement of the pauper’s deceased husband in Cury. The deceased being born in 1819 was in or about 1831 hired, by agreement made in his behalf by his mother, to Mr. James Randle of Colvenor, as a yearly servant; and in two subsequent years, he served in a similar way, by fresh agreements made in his behalf by his mother.

In support of this case, Mr. SHILSON examined Ann Lanyon, aged 75 years, mother of the deceased Thomas Lanyon; and Samuel Hendy, aged 40, who at the time of Thomas Lanyon’s service with James Randle, was living with his father at Sawanna, within one field of Colvenor, and was in the habit of seeing Thomas Lanyon at labour on the farm; and the COURT, on the evidence adduced, held that the settlement in Cury had been made out.

Mr. CHILDS proposed to rebut the evidence of dates by counter evidence. He would show that at the time Lanyon went into the service of Randle, he was of the age of 14 years, and consequently, on the evidence of his birth in 1819, the time of his entering that service was in September 1833, and the conclusion of the year’s service would not have been until after the passing of the Poor Law Act, in August 1834. This evidence of the period of service would be corroborated by an account book, belonging to Mr. James Randle of Colvenor, who would also prove that Lanyon was not in his service more that twelve months. If these facts were substantiated, then the respondent’s case was fully made out; while the appellants could not maintain their case, unless they showed, without doubt, that the alleged settlement in Cury was clearly prior to the passing of the Poor Law Act.

The witnesses called and examined for the respondent, were Mr. James Randle of Colvenor; his servant Martha Rogers; and his son Samuel Randle, now living at Stithians.

The Court held that the settlement in Cury was gained previous to the statute of August 1834. Order quashed, £5 costs.

Source: Royal Cornwall Gazette 11 April 1856 (Cornwall Easter Sessions)

Transcribed by Karen Duvall – Reproduced with the permission of Cornwall OPC https://www.opc-cornwall.org/index.php

It’s quite a distance to remove someone from their family and friends.

By 1861 (source – the census) Louisa Lanyon (a charwoman) was living in St Allen with her mother Ann Williams (a charwoman) and her son John Henry who was 13 and working as an agricultural labourer.

By 1864 at the age of 43 she was dead. In 1868 Ann Williams was dead. We don’t know what happened to John Henry Lanyon, did he die, did he emigrate, did he use a different name? There is a John Henry Lanyon who died in Lincolnshire in 1935 is it the same person?

What happened to his half brother and sister?

James Lanyon 1841-1883 married Mary Ann Kempe. He worked as an agricultural labourer and they never had any children.

Mary Ann Lanyon 1842-1908 married Richard Grigg, a carrier, in 1883 at Penzance and they never had any children.

Perhaps becoming orphans put them off ever having children of their own.