On the 3 Dec 1973 William (Bill) Lamparter wrote to Peter Pool, the editor of the Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall inquiring if they would be interested in publishing an article which he had ‘very nearly completed’ on the origin and development of the Lanyon surname and Lanyon coat of arms. Peter Pool responded that the next journal due for publication in Summer 1974 was ‘virtually full’ and they would probably defer it until the following year. By November 1975 Bill wrote to Peter ‘I am embarrassed and chagrined to have to write to tell you that my Lanyon article is still not complete…’

By 1978 Bill was still collating information for his article! I don’t know if it was ever actually published but I have taken the ‘article’ he wrote, the amendments, notes and additional information and produced this article so that the information is not lost. His references were incomplete, I’ve noted which were blank and submitted my own contribution in brackets.

Observations concerning the origin and history of the Lanyon surname and coat of arms in England and in the United States of America 1215-1974

By William Lamparter

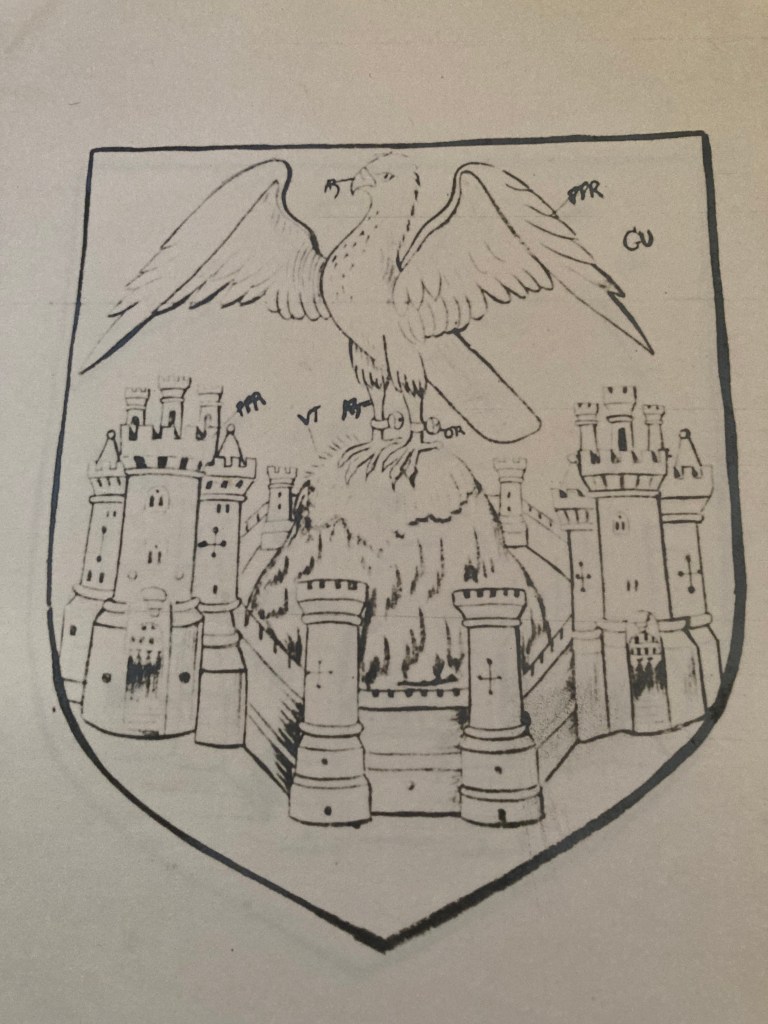

The earliest extant record of the Lanyon coat of arms so far identified is the painting made following the first visitation into Cornwall by the King’s Heralds in 1530. It is blazoned, Gules, a square castle in perspective with four towers argent, a falcon, proper, belled, beaked and legged azure, rising from a mount vert in the courtyard of the field. It has been noted that this record or entry was not a grant of arms but, rather, the Heralds’ record of arms presumably already used by the Lanyon family. (1)

Inevitably, one might suppose that the origin of a coat of arms might in some manner be linked with the family name. If so, probably the precise connection between the Lanyon surname and their arms, if any, will never be known. It will be useful, however, to set forth the various theories of the name origin and, from that display, to derive certain data which might be useful for continuing research, for drawing conclusions or which will, finally, lay to rest various fanciful conjectures as to the origin of both.

It has been said that the Lanyon coat of arms is a purely Tudor creation (2) exhibiting none of the characteristics of earlier and feudal creations or grants of arms. Certainly, the blazon is more elaborate and imaginative than arms typically in use in England during the sixteenth or earlier centuries. Yet there is an old tradition concerning the coat of arms which bears repeating.

On 3 June 1350 at Westminster the earl of Lancaster issued to John de Lynyen a ‘pardon for the good service in Gascony in the company of Henry, earl of Lancaster’ (3). It was theorized by Miss Mitchell (4) that the Lanyon coat of arms in some manner depicts the feat or role performed circa 1350 in Gascony for which John, this early Lanyon, was granted pardon from some earlier misdeed. No fact supports this conjecture, however attractive it is, but the conjectural association of the Lanyon surname as having been derived from the lanner, or falcon, coupled with the appearance of the falcon rising from the mount in the coat of arms does nothing to diminish the tradition concerning the arms’ origin. In ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’ by William Bottrell (1873) an old tale is recorded of an elderly Lanyon, living in Lamorna, whose house, while sparsely furnished, retained some memorials of former ancestors, including a ‘huge pair of jack boots which belonged to some renowned ancestor.’ One would like to think that the boots had been worn by John de Lynyen in Gascony, perhaps while performing his ‘good service’, which might have been commemorated on the Lanyon coat of arms. Very probably we shall never know.

It was of course Hals (5) who brought up the matter of the Lanyon surname having been derived from the lanner; the species of falcon presumably portrayed on the coat of arms. Neither etymologically nor in any other way, however, does there seem to be the slightest shred of evidence to support that theory. Three other possible derivations of the name which have been proposed have merit. The first, although not necessarily the oldest, appears (among other places) in ‘The First Book of the Parish Registers of Madron in the County of Cornwall’ by George Bown Millet (6) wherein it is proposed that the association of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem with the parish of Madron may have in some way provided the names origin. This theory offers that the surname, Lanyon, may be derived from a compounding of two distinct Cornish words, the first, lan, meaning a monastic enclosure (7) or a ‘level spot, an enclosure, a sacred enclosure, a monastery, a church.’ (8) And Lan as a surname John. (9) {Lan-john….John’s enclosure.}

A second possible derivation of the Lanyon surname is as intriguing. It was William Hals who, in the middle of the eighteenth century wrote:

‘Lanyon, in this parish (Gwinear), a seat of the Lanyons, the first propagators of this family in Cornwall, came, with many other French gentlemen, into England with Isabella, wife of King Edward II, and settled themselves in those parts; amongst which Lanyon’s posterity have ever since flourished in gentle degree in Cornwall; and for further proof of this matter, that originally they came from the town of Lanyon, situate upon a sea-haven, or harbour, in France, they still give the arms of that town for their paternal coat of armour, viz. in a field Sable, a castle Argent standing on waves of the sea Azure, over the same a falcon hovering with bells. The present possessor Tobias Lanyon, Gent, that married Pineck (sic); his father Reynolds.’ (10)

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The theory or conjecture is, of course, an attractive one, but Hals, or his helpers, if he had any, had not discovered that the Lanyons were in Cornwall by 1215 (11), whereas Queen Isabella came to England only in 1307, a few months after Edward II’s accession to the throne. Yet the matter does not end there. Indeed, there is a small city in Brittany (Department Cotes du Nord) called Lannion. Further, there is an old and distinguished family of that name in Brittany which has been said to have ‘….tire son nom de la ville de Lannion. Elle a toujours été considérée dans cette province comme une des plus distinguées parmi la meillure Noblesse.’(12) This family, carefully documented up to the end of the eighteenth century, was descended from the barons of Avaugour (13) who were, in fact, the enormously powerful and preeminent house of Penthievre whose descendants, after their despoilation by Pierre de Dreux, assumed the name Avaugour. (14)

To continue this point however, it will have been noted that Hals, as quoted by Davies Gilbert, states that the Lanyon coat of arms is identical to that of the Breton city of Lannion (15). So far as can be ascertained, there is no basis in fact for his statement. The coat of arms of the city of Lannion is blazoned as Noir, a lamb couchant, holding a pennant etc. One wonders where Hals derived his information. Assuredly, the 1530 Lanyon coat of arms does not owe its parentage to those of the city of Lannion although the Cornish family of similar name may.

The tradition of a French, or more specifically, Breton or Norman family origin will not die easily among contemporaneous Lanyon descendants if, indeed, it is firmly and finally established that the Lanyons of Cornwall had an indigenous origin. Just as so many Lanyon-descended households in England and in America embrace one or several reminders of their inhabitants’ Cornish origin – a photograph of the Lanyon cromlech, one or another version of the coat of armour, a photograph perhaps of Lanyon in Madron or Gwinear – as many households cling closely to the romantic but so far undocumented tradition of a French descent. Typical yet surely not unique, is a letter dated 10 March 1911 (16) from John Lanyon (17) to Harry Theodore Sherwood Smith I. The letter was written in reply to an earlier one from Mr Smith to Mr Lanyon enquiring whether the latter was in any way connected with the Lanyons of Cornwall, explaining, apparently, that Smith’s wife had been born a Lanyon. (18)

‘The Lanyons originally all came from one stock, and they are an old French family. At the time of the conquest, Jean Lanyon was supposed to have been one of the Knights of William of Normandy afterwards known as William I of England. Some of his descendants settled in the South of England and other members of the family came over to England at various times after. I am directly descended from the Frence (sic) branch.’

A third possible derivation of the Lanyon surname is purely Cornish. In ‘A Guide to Cornish Place-names, with a List of Words Contained in Them’ Robert Morton Nance proposed that the name might have been derived from compounding two Cornish words, Lin – meaning pool or pond and eien – meaning cold, while adding that why the pool should be particularly cold is unknown (19). As might be expected Nance did his homework well: a look into Borlase’s Cornish vocabulary (20) reveals the existence of these words, however, it was Nance who apparently first identified the compounding and, indeed, there still remain traces of a pond at Lanyon in Madron – probably in the seventeenth century, and possibly earlier, it was a source of water-power for the mill, now in ruins, down towards Bosullow. John Tregarthen in his novel ‘John Penrose’ written about life at Lanyon in the nineteenth century mentions the pond in a topical and amusing way (21). If Morton Nance’s interpretation is accepted, one must assume an indigenous and non-Breton origin for the surname.

A brief review of a few of the early documents relating to the Lanyon family will provide a certain insight into the origin and evolution of the surname. In considering the evidence of these documents and in reflecting upon the origin and meaning of the surname, it is important to consider always that while contemporary orthography tends toward Lanyon, and pronunciation toward Lan-Yawn, even within memory, Lanine, pronounced La-Nine, was neither unknown nor uncommon, although the latter usage, it must be granted, was rather more typically Cornish than English or American.

In the earliest document known which treats of the family dated 1215 (22) appear Agnes, who was the wife of Roger de Leniein, then a widow, and her son, John de Linien. Roger’s name later in the same document, is written Lenien. This transaction had to do with the family property variously spelled as Lennein and Lenien. Nowhere in these names does the later ‘Y’ appear.

Nearly thirty years later, in a foot of fines, John de Linyeine again appears, with an alternative nomenclature. (23) Here the first letter or vowel or the second syllable has mutated to ‘Y’.

There are other examples. In 1350, over one hundred years later, another John has his surname written Lynyen (24) a cluster of ‘Ys’. Toward the end of the fourteenth century, Bishop Brantyngham granted a licence to celebrate mass ‘….in Capellis Beate Marie, do Laneyn, necron Sanctarum Brigide et Morvethe infra Parochiam suam situatis;….’ (25) Surely the pronunciation would have been La-Nine or possibly La-Nin-en.

A century later, the surname was being spelled Lanyeyn, as appears in a letter of attorney dated 23 October 1462. (26) Quite possibly this spelling derived from a trisyllabic pronunciation, as La-nye-in.

It was in fact, not until the nineteenth century that the commonly accepted spelling of the surname in Cornwall became Lanyon. In America the name is not known in any other form.

This, then, in summary, is what is known concerning the possible derivation of the Lanyon surname and, briefly, the origin of their coat of arms. Much of it is theory, indeed speculation, all of it is subject to further research and particularly the conjectural Breton origin. We may now turn to matters of fact.

Historical research moves itself out of the area of speculation by documentation and physical fact. We need to look at how, where, and in what ways the Lanyon coat of arms was employed by those who inherited it.

Sometime prior to 27 February 1554, John Rashleigh of Fowey, Esq., married Alice (27) daughter of William Lanyon of Lanyon, Esq., by his wife Thomasin, daughter of Thomas Tregian. The Rashleigh history is well enough known and needs no recitation within the scope of this paper. Perhaps the Rashleighs of Fowey, an increasingly successful mercantile family, later of Menabilly, were particularly pleased with their alliance with this old family of Cornish gentry; the manner in which they celebrated it on the tomb of John Rashleigh, senior, and upon the monumental brass of Alice Rashleigh, would indicate so. Alice Rashleigh died 20 August 1591 and her remains were interred in the nave of St Fimbarrus Church, Fowey. A brass effigy and inscription plate are embedded in part of the stone flooring of the church, but a shield above the effigy is missing. One would give much to see it (28). Like much else, it is gone, forever. Nearby, however, seemingly intact, remains the monument and tomb of her husband, John Rashleigh, whereon appears the Rashleigh coat of arms, Quarterly Sable, a cross Or between a Cornish chough Argent, beaked and legged Gules, 1st quarter; in the second quarter a text ’T’ of the third; 3rd and 4th, a crescent of the last, on the cross in chief a rose impaling those of the Lanyon family (29). This is the unique monumental example of how the Lanyon arms should be displayed, at least when compared with the 1530 drawing in the College of Arms (30). On the tomb the Lanyon arms are shown in perspective, as originally recorded, and not symbolically, as is the usual instance.

There are other examples of the Lanyon coat of arms extant in Cornwall. Many more are blazoned in the histories. Most of them are incorrect.

The coat of arms over the porch at Lanyon in Gwinear is, however, heraldically impeccable. Well maintained, it is dated 1668. It does, notwithstanding, differ materially from the Lanyon arms first recorded in 1530, one hundred and thirty-eight years earlier. The castle is not in perspective but, rather square; the mount has disappeared; the castle rests on waves of the sea; the falcon wears no bells. By 1668, a younger branch of the Lanyons were well-established at Gwinear. It appears that Edward, fifth son (31) of Richard Lanyon of Lanyon. Esq., by Margaret, daughter and heiress of Thomas Treskillard, was living at Gwinear in the late sixteenth century. His children were being baptised in the parish in the 1590s. In fact, it might be stated that the Lanyons, after the mid 1500s, did not regard Lanyon in Madron as their principal residence. They owned much property elsewhere in the county, acquired by inheritance or by purchase. Lanyon in Madron may have been uncomfortable; it is, still, windswept, bereft of trees and, no matter how attractive in certain seasons it must have been cold in the 1500s. Judging from the Gwinear parish registers, it was Richard, father of Edward, who moved his principal residence from Lanyon, Madron to Lanyon, Gwinear. He and his wife were buried there, in 1592 and 1579 respectively (32).

Richard, interestingly enough, seems to have attempted to make adequate provision for all his children, so far as can be judged. John, the eldest son and heir, continued at the Madron estate, as was his right. William the fourth son was granted the Tregaminion (33) property, in westernmost Cornwall, by his father and eldest brother. Edward the fifth son was situated at Lanyon, Gwinear, where his descendants remained until circa 1785 (34) when the estate was sold. By 1668 Richard the father had been deceased by seventy-six years. His descendants in the eldest line, (John, Francis, Richard and John) disappear finally in St Ervan at Treginegar (35), another of the Lanyon properties. The cadet branch at Gwinear, meanwhile, flourished. Whether this manor house there was constructed in 1668, the date above the coat of arms placed over the principal doorway, or whether the house was considerably older, the date representing merely the year of reconstruction, needs to be established. At any rate, it appears that Tobias Lanyon of Lanyon in Gwinear, Richard’s great grandson, had his coat of arms erected above the entrance to his manor house, either upon construction of the building or upon its renovation following the period of the Commonwealth, when it is said, many houses of the area were rebuilt.

As early as 1602, Richard Carew wrote in reference to the Hundred of Kerrier, that:

‘Divers other gentlemen dwell in this hundred; as Lanyne, the husband of Kekewitch; his father married Militon, and beareth, s. a castle, a. standing in waves b. over the same a falcon hovering with bells o.’(36)

The Lanyon coat of arms over the principal entryway at Lanyon was placed there in 1668, sixty-eight years after Carew wrote, yet it accords precisely with the arms described by that historian. Carew was writing, of course about the Lanyons who lived in Breage parish, gentry which achieved financial and political success outside their county as merchants, politicians and courtiers in Plymouth and London, quite possibly, however this blazon was employed generally by the younger branches of the Lanyon family. There is no evidence that the ‘waves of the sea’ were ever incorporated in the coat of arms of the senior branch.

In St Bartholomew’s church in Lostwithiel, is a handsome monument to the Doctors Lanyon, even yet of distinguished memory in the area. This memorial incorporates, at its base, the Lanyon coat of arms, quartering Trelissick and Militon. The Lanyon arms, however, differ notably from the coat of arms erected over the porch at Lanyon, Gwinear. The waves of the sea disappear; the castle is more or less in perspective; the mount rises from the castle courtyard and the falcon rises from this mount. In fact, as will have been noted, these arms are virtually identical to those shown in the 1530 drawing. One wonders why, with the evidence of the Gwinear Lanyon arms readily available over the doorway at nearby Lanyon, those responsible for the creation of the church memorial would have reverted to arms used at least 319 years previously, and clearly not those of the Gwinear branch. The coat of arms quarters the arms of the Militons of Pengersick castle, thus probably reflecting a traditionally accepted descent from that family. Unfortunately, however, at least for the sake of monumental accuracy, the Gwinear Lanyons were not descended from the marriage between John Lanyon of Lanyon and Philippa daughter and coheiress of William Militon of Pengersick and the Gwinear branch was not entitled to quarter the Militon arms. The quartering of the Trelissick arms on the shield of the monument is, however, entirely correct, since all branches of the Madron Lanyon so far identified descend from the marriage of Richard Lanyon of Lanyon with Isabell daughter of David Trelissick.

The monument was erected sometime following the death of Richard Lanyon, M.D. on 10 September 1850. He and his father, another Dr Richard Lanyon who died on 19 April 1848 were memorialised on this monument, commissioned by their heir, Rodolphus Edward Lanyon. The tablet is signed at the left-facing base “Edgecombe” and at the corresponding right-facing base “Truro”. It would appear however that by the mid-eighteen hundreds the surviving members of the Gwinear Lanyon family had lost the precise details of their descent heraldically or otherwise.

Sacred to the memory of Richard Lanyon, Esq., Surgeon, &C. He was descended from the ancient families of Lanyon in Madron and Gwinear, and having

passed a long life in the active discharge of the most philanthropic and Christian duties, and filled the highest offices in the corporation of this town, died

on the 19th of April, 1848; æt. 82.

As he lived, so he died,–a Christian.

Also of his son Richard Lanyon, M.D., F.A.S., &c., who for many years successfully practised his profession in his native town, where he was well

known for his antiquarian researches, and his literary and scientific attainments ; he also zealously and usefully filled the highest offices in the corporation,

and died humbly relying on the merits of his Redeemer, Sept. 10th, 1852; æt.53.

This monument is erected by Radolphus Edward Lanyon, as a tribute to their worth, and a mark of his gratitude. (Not part of the original article.)

It must be noted that these Lanyon families may have developed the simpler castle design because of the difficulty of reproducing the castle on the coat of arms in perspective. In close-up work, as for example, in the execution of seals, the rendering of the perspective castle is difficult and the newer ‘en plein’ version may have come into use or have been adopted. That evolution no matter how likely, does not explain away ‘the waves of the sea, azure.’ One wonders whether the ‘waves’ were not adapted as a difference by the cadet branches with a reference to the geographical proximity of St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall or, more remotely, to Mont St Michel in Brittany (now Normandy) in a gesture to a faintly recalled tradition relating to the Lanyons’ Breton descent. That is rather fanciful; very probably we shall never know.

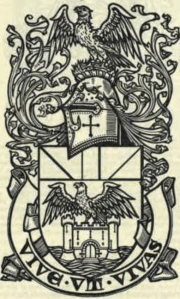

In subsequent years, other interpretations of the Lanyon coat of arms appeared. Bequeathed to me, together with a helpful manuscript collection by Dr E A Bullmore, is a wax and seal impression of the coat of arms of John Jenkinson Lanyon, progenitor of the wrongly called Irish Lanyons. Impressed in red sealing wax, it was sent by Miss Mitchell to Dr Bullmore in 1927 and it is identified by her as John Jenkinson Lanyon’s fob seal of Lanyon arms (18th century). The seal quite closely resembles the arms over the Lanyon porch at Gwinear (except for the shape of the shield) with respect to waves of the sea, castle and falcon. The crest is a falcon rising and there is no motto. A traditional younger branch Lanyon coat of arms. We do not yet know the parentage of John Jenkinson Lanyon, progenitor of a distinguished Lanyon branch but if Miss Mitchell’s statement is to be taken at face value, John Jenkinson Lanyon had in his possession presumably by inheritance, a perfectly valid seal of the Lanyon coat of arms. Even though the traditional descent of this branch of the Lanyons has not yet been documented, the presumptive evidence of their descent from the Cornish Lanyons was apparently sufficient for the Ulster King at Arms to grant Sir Charles Lanyon, John’s son, a derivative Lanyon coat of arms (37). Fox-Davies (38) blazons it ‘Gules, on waves of the sea azure, a castle of two towers, on the battlements thereof a falcon rising all proper, on a chief or, a pallet between two gyrons of the field. Crest – on a mount vert, a falcon rising proper, belled and jessed or. Motto – ‘Vive ut Vivas’.

John Jenkinson Lanyon married Catherine Anne, daughter of Charles Smith Mortimer, Esq. of Eastbourne, Sussex and Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Russell of Eastbourne. The Mortimer coat of arms is reflected in the grant to Sir Charles Lanyon: ‘….on a chief or, a pallet between two gyrons of the field.’

Other, however, and variant Lanyon coats of arms are extant in Cornwall and in America. Some years ago I looked upon these variants with some degree of scepticism as having derived from a total lack of understanding or comprehension of the original coat of arms. Just as, however the Gwinear arms may have been altered for the reasons shown (a difference, a technological difficulty or both) the evolution of the Lanyon coat of arms may have been that: an evolution, based upon an error of interpretation, mistaken reportage, or faulty memory. We are, none the less, faced with the fact too in later days the ‘official’ historians did nothing to assist Lanyon (or perhaps any other armigerous descendants) in blazoning their arms. For example nothing could be more absurd than the Burkes’ 1844 blazon of the Lanyon arms as ‘Sa. a castle with four towers ar. a falcon, hovering, with bells ppr. Crest – on a mount vert. within a castle with four towers ar. a falcon standing on waves of the sea az. above volant, ppr.’(39). The crest itself is a remarkable product; one wonders about those waves of the sea azure sparkling above the mount vert with the Lanyon falcon standing thereon. In the 1878 blazon, the crest remained the same, but the arms are describes as ‘Gu.,on waves of the sea az. a square castle in perspective, with a tower at each corner or, in the courtyard of the field a falcon ppr. rising from the mount vert.’(40). The source given is the 1620 visitation however in the ‘Visitation of the County of Cornwall in the year 1620’ edited by Vivian and Drake, the Lanyon arms are blazoned as ‘Gu. on a square castle in perspective with a tower at each corner or, a falcon p’pr rising from a mound Vert in the courtyard of the field.’(41).

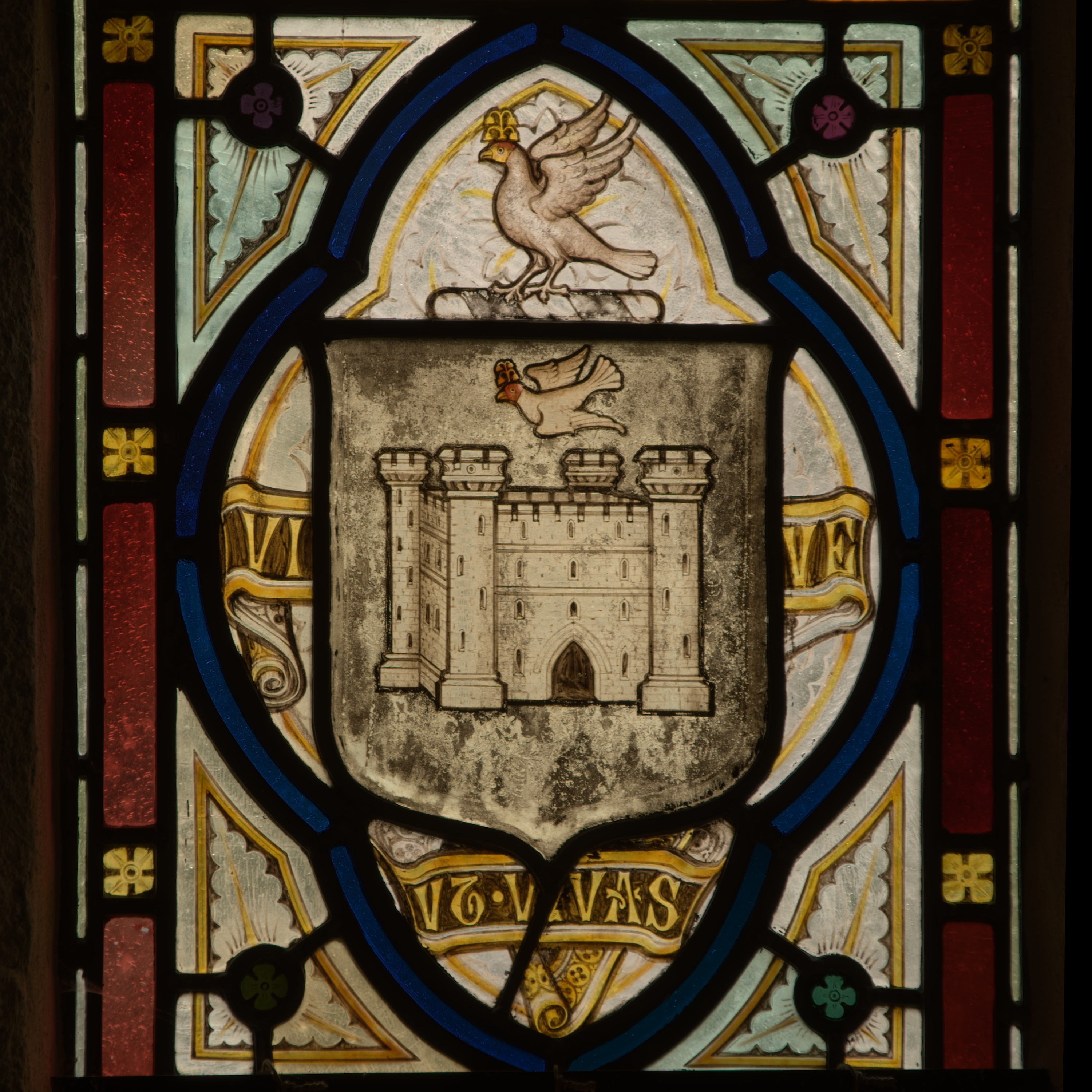

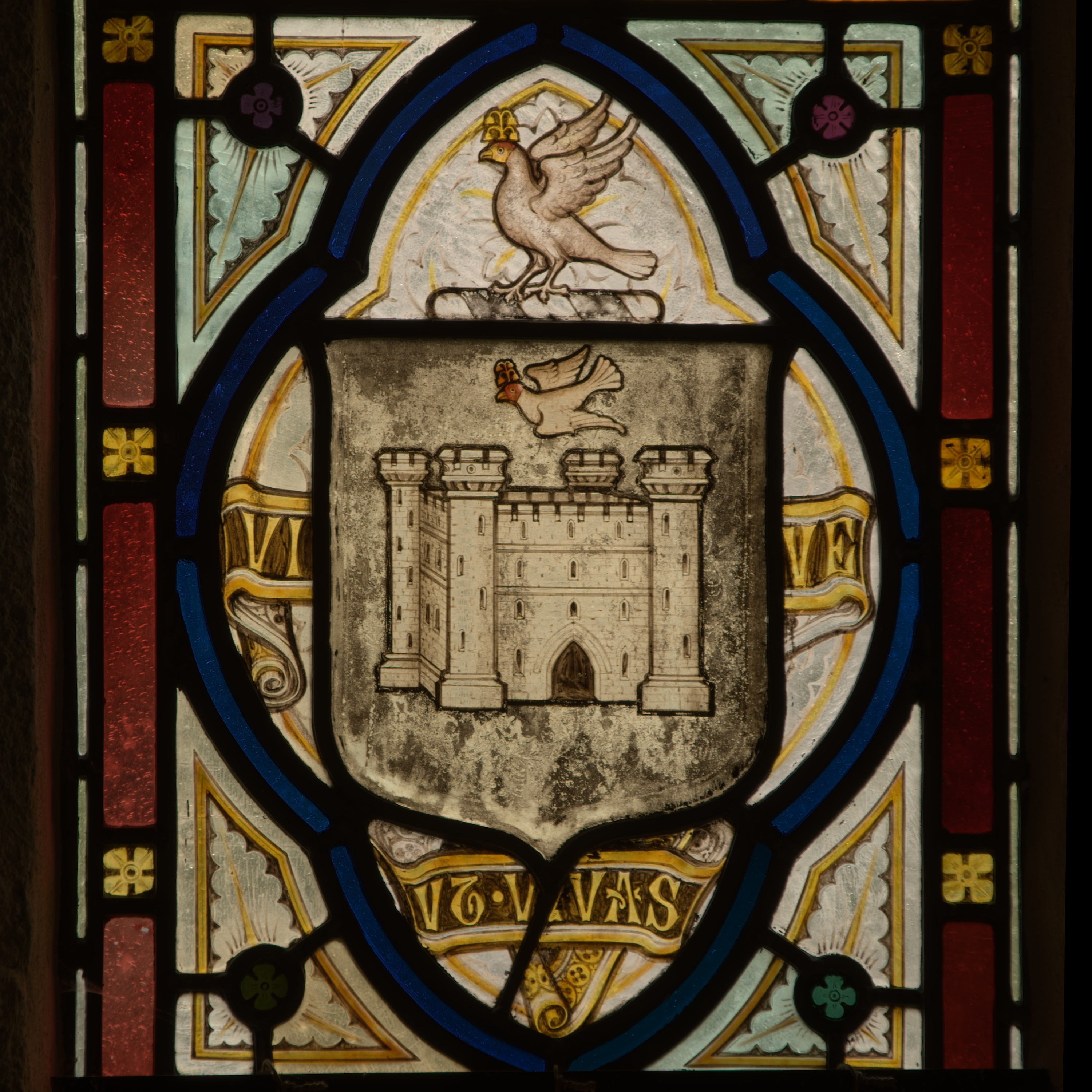

Seemingly this description compounds error upon error to the point of heraldic absurdity with the castle set at an angle (in perspective?) and repeated as the crest. Interestingly enough, the St Allen Lanyons seem to have adapted the Burke blazon of the Lanyon arms as theirs and in one of a series of striking stained-glass windows in St Allen parish church, dedicated to various members of that family, the Lanyon coat of arms is shown in what must be regarded by constructionists in a highly unusual manner. Who, however, is to say that even without official sanction that display is not quite valid as sanctioned by Burke, who however careless in his methods carried with him the authority of the establishment (42). Too, it will be recognised, the evolution of a coat of arms over several hundred years might be subject to the interpretation of the various artists who perhaps with little or no heraldic education and depending upon the perhaps faulty memories of the possessors of the arms, might have been unable to reproduce the nuances of complicated blazons on funerary or other monuments or memorials.

The St Allen Lanyons did well; one needs only to visit their houses, still well preserved, in order to judge. Too, in America, many of their descendants are among our more prosperous and finer citizens. It does not, however, necessarily follow that these Lanyon descendants were heraldic experts nor, indeed, that either they nor the artisans whom they employed were so skilled. One might proceed one step further and suggest the interpretation and evolution of arms as a matter of folk art. That expansion is beyond the scope of this paper.

But to pursue, for the moment, the conception of heraldry as folk art, in May 1972 I was again in the St Allen church with a St Allen descended cousin and her husband both of whom are skilled amateur photographers. During that visit, and a subsequent one, they took many pictures of the Lanyon windows in the church. It was not until they visited my home a year and a half later, when they showed the photographs to me that I noticed an unusual and I believe unique alteration to the traditional Lanyon crest: the expected Falcon held in its beak a tiny cross or. Never before, nor since seen in Lanyon heraldry. One wonders now what family member, what artist, added this charge and why. Surely without sanction of the College of Arms and thus perhaps without collegiate validity. Yet as folk, or even personal art, a fascinating development in the evolution of the Lanyon coat of arms, at least borne by St Allen Lanyons. One acknowledges here the public lack of distinction between an inheritable coat armour and a non-inheritable coat of arms including a personal crest which qua crest, may vary from one possessor to the next.

Study of the manuscripts of the late Charles Henderson, housed in the Royal Institution of Cornwall has been helpful. His sketches or tricks of the wax impressions of the Lanyon coat of arms used by the various Lanyons of west Cornwall reveal that there was no uniformity in their employment. It is quite apparent that each of the Lanyons entitled to the use of the arms employed or displayed the coat armour in a slightly different manner. One wonders whether these variations are attributable to the skill and imagination of the seal engraver, or to some wish by the possessor for his personal ‘difference’.

These are additional notes which were intended to be incorporated into the article.

Aide Memoire – 14 Jun 1978

On Tuesday afternoon, 9 March 1976, I called at the College of Arms, Queen Victoria Street, London and was received by P.Ll. Gwynn-Jones, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant. The purpose of my visit was two-fold: first, to reintroduce myself to the college of Arms where I had twice previously visited, circa 1949, with (now Sir) Anthony Wagner and, some years later, with Mr. Trappes-Lomax, now deceased; second, to enquire concerning the Lanyon family coat of arms incorporated in two stained glass memorial windows in the St Allen parish church in Cornwall.

Among my Lanyon papers is a typewritten copy of what appears to be a copy of a newspaper article relating to two of the Lanyon memorial windows in the St Allen church. The typescript is headed ‘The Lanyons from Henver and St Allen Church’ – from the Cornwall Advertiser. The principal subject of the paper is a window erected in the St Allen Church in 1889 by Simon Henry Lanyon {in memory of John & Peggy Lanyon (43)} and of his father, Simon, their fourth son. The article continues:

‘This is the second window in this church in memory of the Henver Lanyons. The first is to the memory of Henry and Isabella Lanyon, the said Henry being cousin and Isabella the sister of the above-mentioned John Lanyon and the parents of Miss Henrietta Lanyon, of Truro, a lady well known for her gifts to Truro Cathedral, especially the donor of the beautiful lectern bearing her name.’

Enough is known of these nineteenth century Lanyons and Henrietta’s lectern with its Latin inscription is still in Truro cathedral. The article, however, fails to mention that there are, in fact, two memorial windows in the St Allen church, one dedicated to Captain Henry Lanyon R.N., and the other to his wife Isabella Lanyon. The newspaper article implies an installation date earlier than 1889; the window dedicated to the husband reads ‘Henrici Lanyon R.N’ and ‘obit 8 Decembris 1862’, while that dedicated to the wife reads ‘et Isabella Lanyon’ and ‘obit 18 Maii 1852.’ The windows dedicated to Captain Lanyon and his wife flank the altar. One would like to think that they were installed simultaneously; if so, the date of their erection may be placed between 1863-1889.

It is these two windows to which this paper is addressed and, more specifically, to the identical coat of arms of the Lanyon family incorporated in each window.

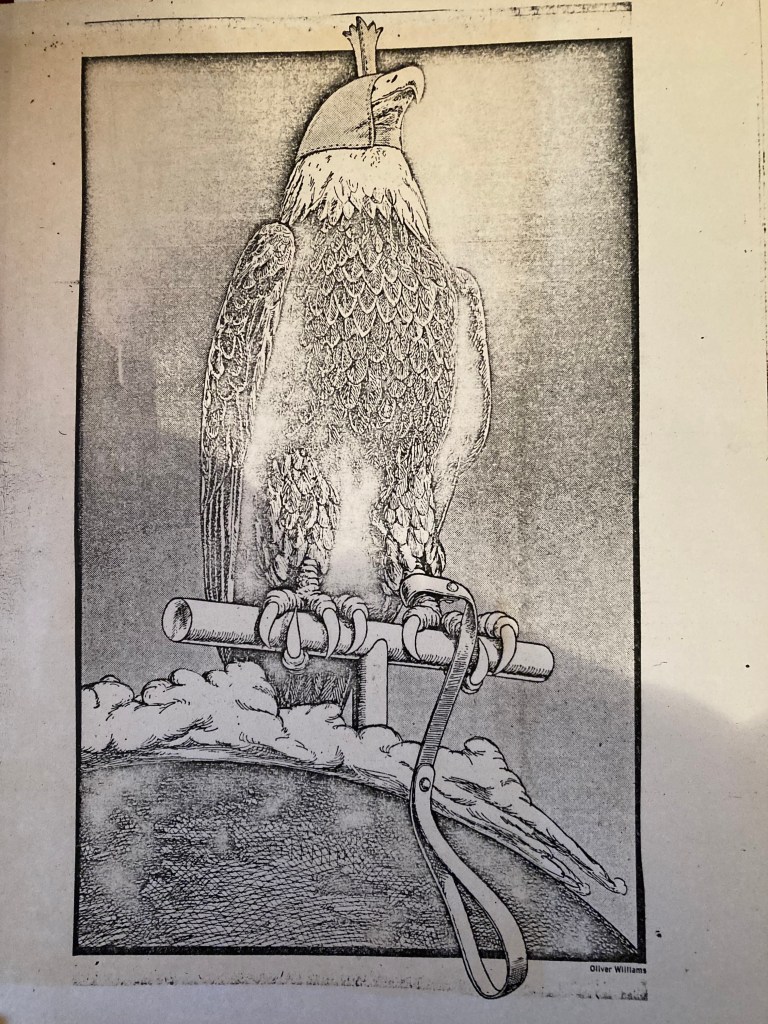

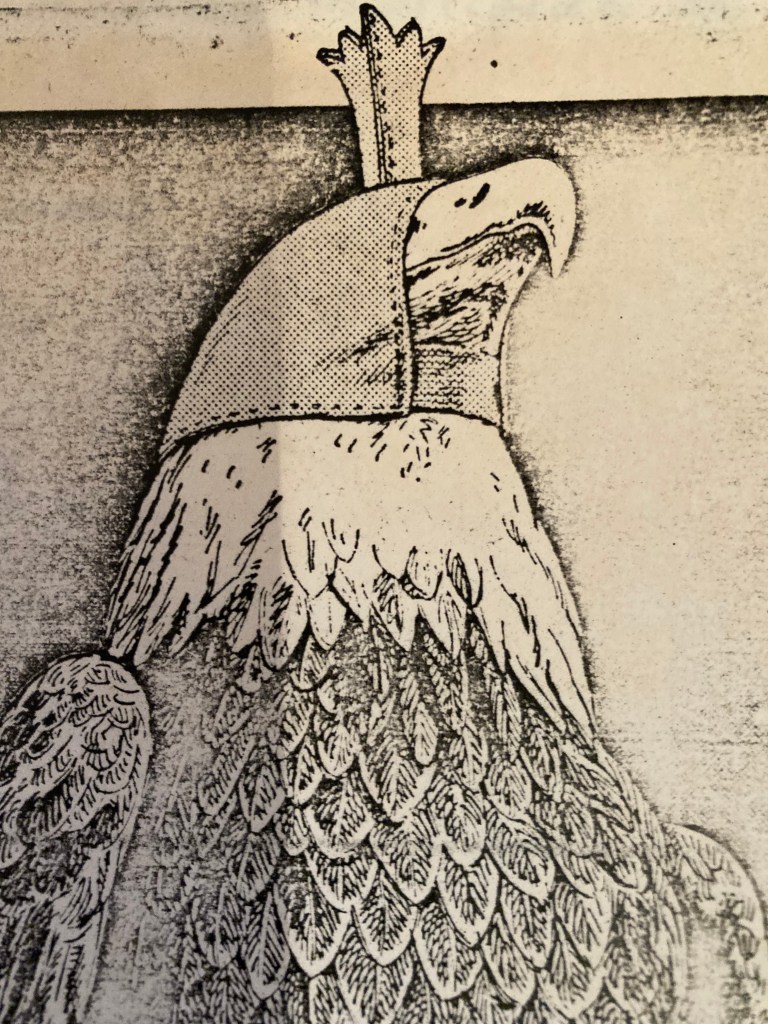

The bird traditionally associated with Lanyon heraldry is a falcon proper. This is true whether the bird is shown on the shield, rising from a mount vert, as in the 1531 painting of the coat of arms at the College of Arms, or whether shown on the crest. The birds in the St Allen windows under consideration, however, are white and, indeed, more resemble doves than falcons. As well, their heads, from necks to tops, including beaks, are or, a combination not seen elsewhere in Lanyon heraldry. Finally, in these memorial windows, a curious and indecipherable object rests on the tops of the heads of these interesting birds.

I submitted this problem of interpretation, as illustrated by the colour photographs taken in 1973 by Emily. B. Lueck to Mr Gwynn-Jones. He suggests that the design for the coats of arms which appear in the two windows was probably first shown to the artisans who executed the windows by means of a drawing by an artist who was perhaps unfamiliar with heraldry, or blazonry, and who had mistaken the traditional Lanyon falcon as a white dove, rising, with a nimbus of the same, superimposed by a cross, or. While admitting the possibility of artistic license, as well, Mr Gwynn-Jones points out that ‘the bird which the artist has possibly mistaken for a dove, as indicated by the white colour of the bird, has a nimbus or glory behind its head. However, the bird is also hooded which suggests that the nimbus is derived from an erroneous interpretation of the crest or feathers which were often placed on top of a falcon’s hood, with a curious result.’ Whatever the artist’s intention, each of the birds as shown in the St Allen church in both windows, on the shields as well as on the crests, must be described as ‘a bird, white, hooded or, with a nimbus, white, on which is superimposed a cross, or. (Bells, Beaked and Legged.)

The castle design on the St Allen shields is interesting as well, although not unique as are the birds. The dimensions of the castles shown on the two shields are nearly as monumental as those shown in the painting of the Lanyon arms taken during or shortly following the Herald’s Visitation of the County of Cornwall in 1530. The four towers are present, but the structure is not drawn ‘in perspective’, as Vivian describes, and the castle is drawn as a large, fortified structure of great height, crenelated, multi-fenestered (sic), the principal entry through a pointed archway. No ‘courtyard’ is shown, obviously, therefore, the ‘mount vert rising from the courtyard of the field’ is omitted, and the bird above the St Allen castle must be described as ‘volant‘, rather than, as in the original painting, ‘rising’ or, as sometimes, ‘hovering’. Too, and curiously, particularly when considering the potentials of stained glass, the traditional and vivid coloration of the received coat of arms, and its variants, are missing from the St Allen coat of arms which is executed chiefly in white, gold, and black. This is especially noteworthy when considered with respect to the other St Allen Lanyon windows, richly furnished with red, blue, gold and even black colorations and might well be an indication that the sketch from which the windows’ creators worked was executed in black and white rather than in colour or, even, blazoned.

The origin of the Lanyon coat of arms has for years been a matter of conjecture, often fanciful. As will be seen elsewhere, it was the historian David Gilbert who, in 1838, stated that ‘…they {the Lanyons} originally…. came from the town of Lanyon, situate upon a sea haven, or harbour, in France {and} they still give the arms of that town for their paternal coat armour, viz. in a field Sable, a castle Argent, standing on waves of the sea Azure, over the same a falcon hovering with bells.’

This is a widely repeated theory. To date however there is no evidence to support the assertion. In discussing the possible origin of the Lanyon coat of arms with Mr Gwynn-Jones, however, he observes that it seems quite likely to him that the arms might have been an adaptation or a copy of some kind of corporate seal. His observation suggests a re-evaluation of Mr Gilbert’s assertion. More factually, however, is our knowledge that when the King’s Heralds recorded the arms of Lanyon of Lanyon in 1530, it was simply a recording of arms already in use and not a fresh grant.

There is also this note to be incorporated into the article:-

‘Lanyon, properly Lanion, from Lan-eithon, the furzy croft.’

References: Sadly the notes and references are incomplete, I have filled in blanks where they are known.

- Lanyon MSS letter dated ? From JAVIM to Dr EA Bullmore.

- This suggestion was first put forth to the author during his visit to Dr EA Bullmore in Falmouth Cornwall in Sep 1948.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls PRO- Edward III, Vol VIII

- {Left blank}

- {Left blank}

- {Left blank} (note- the digitised book is available on Cornwall OPC website – Madron parish – bottom of the page.)

- A New Cornish-English Dictionary by R Morton-Nance

- Cornish names by TFG Dexter. Longmans, Green. London 1926 p.33

- Ibid p.33

- The Parochial History of Cornwall by daviesGilbert. JB Nichols and Son. London 1838, Vol II p.142

- {Left blank}

- Dictionaire de la Noblesse. De La Chenaye-Desbois et Badier Vol XI, col. 456-60. Paris 1867, 3eme Ed.

- {Left blank}

- {Left blank}

- Gilbert. Op.cit. vol II p 142.

- Lanyon MSS, letter dated 10 March 1911 from John Lanyon to HT Smith, 115 Broadway, New York City.

- John Lanyon was associated with Lanyon’s Detective Agency, 240 Broadway, New York City. There is no further trace of him.

- Harry Theodore Sherwood Smith I, 1971-1940 was the author’s grandfather. He was married to Elizabeth Arthur Lanyon 1870-1954 in Brooklyn, King’s County, New York, on 22 September 1896.

- Letter from R Morton Nance to Edward Augustus Bullmore M.D. original in possession of the author. Copy furnished to the Royal Institution of Cornwall.

- Observations of the Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall by William Borlase. Oxford. Printed by W Jackson, 1754

- John Penrose by JC Tregarthen. John Murray first edition, London. 1923.

- Curia Regis Rolls. Vol VII 1213-1315 Published by HM Stationary Office 1935. Trinity Term 16 John m.12d. p 193

- Feet of Fines. Co Cornwall. 28 Henry III (28 Oct 1243-27 Oct 1244)

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office. Edw III, Vol VIII, 1348-1350. London: HM Stationery Office. 1905. P.548. 24 Edward III – Part II. Membrane 21. 3 June 1350, Westminster.

- Bishop’s Register. Registrum Commune-Anno 21. A.D. 1390. Vol 1. Homajuim. P.697 {Reference supplied by JAVIM. Presumably this was a private chapel. Cf. Magna Britannia. Vol III Cornwall. Daniel and Samuel Lysons. London. T Cadell and W Davies. 1814. P 210.

- Reference in the Royal Institution of Cornwall, 23 October 1462. HD/11/10

- In his will, dated 16 September 1578, John Rayshlygh describes himself as ‘merchaunt’. Proved PCC 6 Nov 1582.

- The Monumental Brasses of Cornwall by Edwin Hadlow Wise Duncan. First published 1882. Reproduced and reprinted in facsimile edition in 1970, Redwood Press Ltd Trowbridge and London

- The Visitation of the County of Cornwall in the Year 1620 edited by Lieut-Col JL Vivian and Henry H Drake, London Mitchell & Hughes 1874 p. 306

- {left blank}

- Not ‘2 sonne’ as given in the Lanyon pedigree in the Visitations of the County of Cornwall, 1530, 1573 and 1620. Edited by Lt-Col JL Vivian. Exeter: William Pollard & Co 1887 p.281.

- {Left blank} (Gwinear Parish Register)

- {Left blank} (Royal Institution of Cornwall 19 Jan 1589 HJ/3/12)

- Magna Britannica Vol III Cornwall. Daniel and Samuel Lysons. London ; T Cadoll & W Davies 1814 p.128

- {Left blank} (Epitome of Exchequer Deposition 10 Chas I Mich 41 (25 Jun 1634)

- {Left blank} (Survey of Cornwall by Richard Carew 1602)

- Lanyon MSS letter in my possession from Major Charley Valentine Lanyon, 30th October 1947

- Armorial Families by Arthur Charles Fox-Davies. London T.C and E.C Jack. 1910

- Encyclopaedia of Heraldry, or General Armory of England, Scotland and Ireland. John Burke, Esq and John Bernard Burke, Esq. London 1844

- The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. Sir Bernard Burke, London 1878.

- The Visitation of the County of Cornwall in the Year 1620 edited by Lt-Col JL Vivian 1874.

- Dictionary of National Biography

- The words John & Peggy omitted in Bill’s text.

Personnae

Edward Augustus Bullmore F.R.C.S., F.S.A., 1875-1948 was an authority on the Bulmer family. In recognition of his contributions to that genealogy he was made a Fellow of the Society of Antiquarians. Through his marriage to Hilda Maude Lanyon, he became interested in the history of the Lanyon family and for some years corresponded frequently with Miss Jane Veale Mitchell of Newquay East. Dr Bullmore, at least in part, apparently underwrote the expenses which Miss Mitchell incurred in researching the Lanyon family history. In 1948, the author, having corresponded with Dr Bullmore concerning Lanyon matters for two years, visited him at his residence in Falmouth and was permitted to borrow many of his Lanyon MSS. including the entire Bullmore-Mitchell correspondence. Upon his death, later in 1948, Dr Bullmore’s youngest son, Dr G H Lanyon Bullmore, wrote to the author to confirm the loan as a bequest by his father.

William Smith Lamparter, M.A., 1926- 1992, the author is descended from the Lanyons through his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Arthur Lanyon. He has been researching the Lanyon family history for some years in Cornwall, London and in America. This is his first ‘published’ article on the family. Mr Lamparter is vice-president of the Century Furniture Company in Hickory, North Carolina.

Jane Veale Mitchell 1866-1929 was a daughter of Samuel Mitchell and his wife Jane Veale Lanyon, and was descended through her mother from the St Allen Lanyons. An indefatigable Lanyon scholar her connection with Dr Bullmore began in 1925 when he wrote her a letter of enquiry following publication in the Western Morning News of an article which she had written about the Lanyons. A lively correspondence ensued, involving suggestions, research and data exchange, lasting until 1929. By that time, Miss Mitchell had prepared and had reproduced, on four large pages, a heavily annotated holographic pedigree of the Lanyon family 1215-1928. Three of these pedigrees are known to be in private possession. The disposition of Miss Mitchell’s Lanyon MSS following her death in 1929 is uncertain.

Article written by William S Lamparter during the 1970s for publication in the Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall.