Having checked almost all the parish registers available for Cornwall I turned my attentions to Devon in my search for Lanyon ancestors. Naturally there are quite a few. Younger sons without a property to inherit may have headed for towns like Plymouth, Exeter or Barnstaple to make their fortunes. Others went to the great dockyards to join the navy or work as carpenters and shipwrights.

It was at Barnstaple that I came across William Lanyon and his family and discovered a part of English history that I hadn’t come across before. Black history in Tudor England.

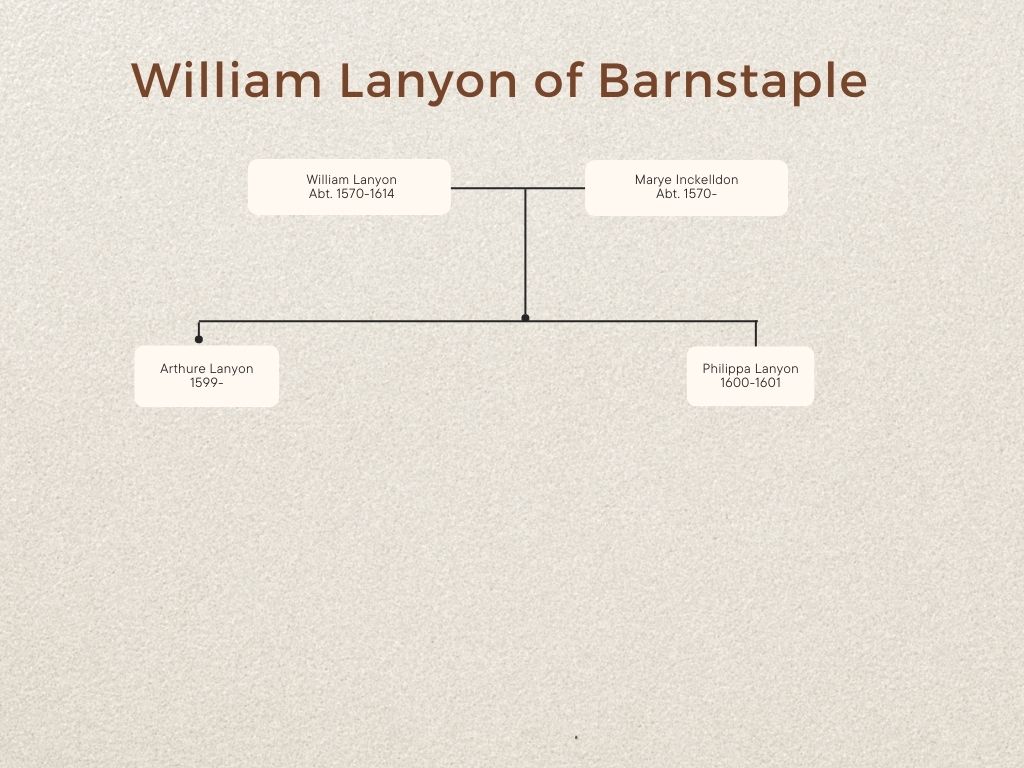

William Lanyon was born about 1570 but I don’t know where or how he fits onto the Lanyon tree. He first appears in Barnstaple’s parish registers on 2 Feb 1596 when he married Marye Inckelldon. Marye was from an old established Devon family, the Incledons/Inckelldons of Braunton. They are listed in the Herald’s Visitations of Devon and the family can trace its roots to the 12th century. Sadly there was no trace of Marye on the Incledon tree.

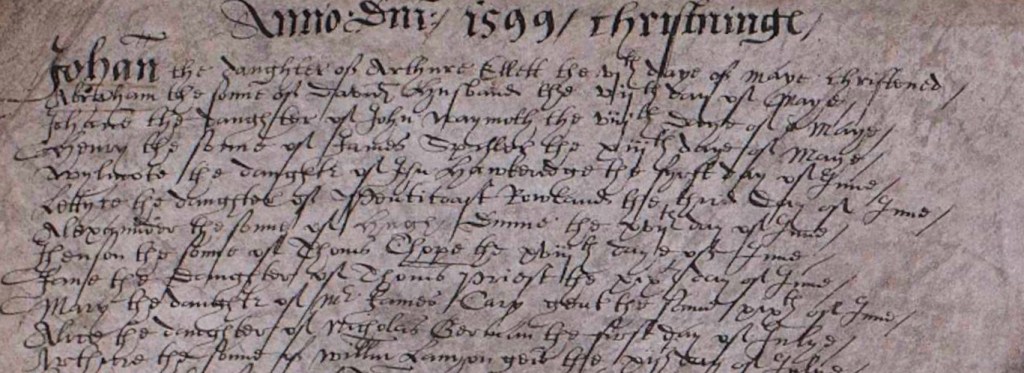

In 1599 William and Marye baptised a son, Arthure at Bideford.

On the 26 Oct 1600 they baptised a daughter, Philippa at Barnstaple and on the 8 Jan 1601 they buried her at the same parish.

William Lanyon was buried in 1614 and that’s all I could find about this little branch of the family.

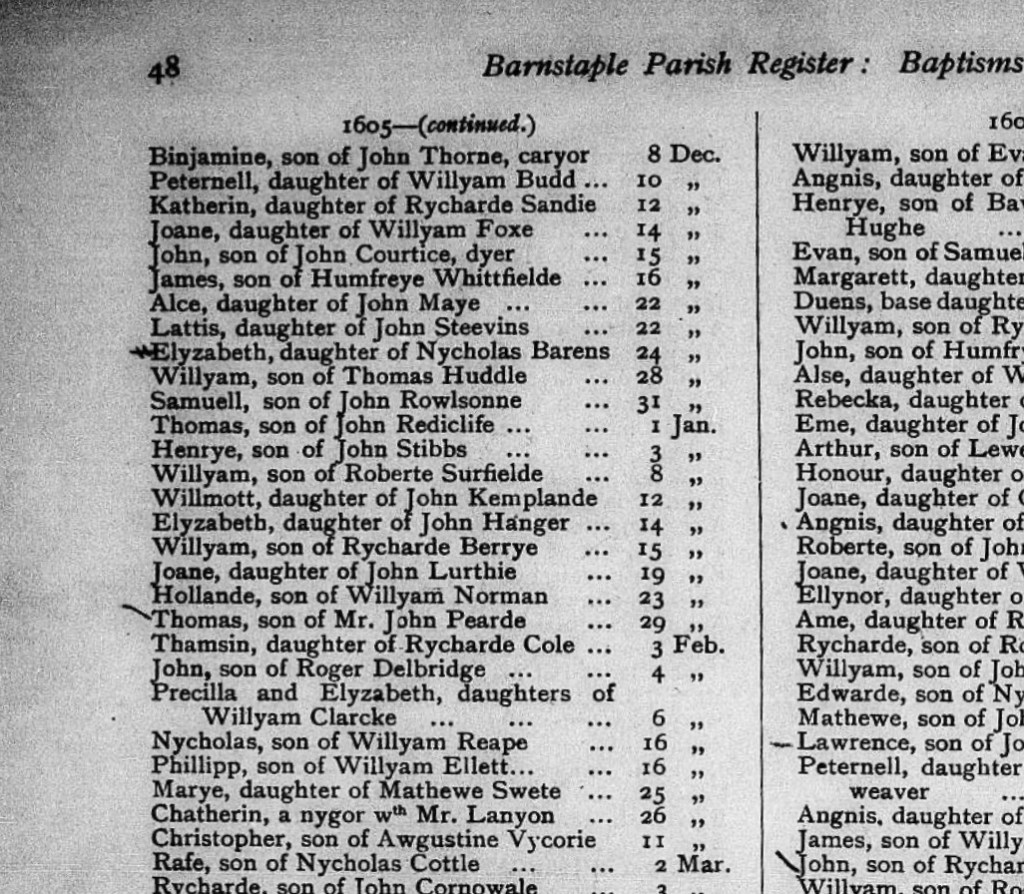

I decided to go through the Barnstaple parish register page by page looking for any information about Arthure or Marye that may have been mis-transcribed and that’s when I stumbled on a whole new area of English history.

My first instinct was outrage that William had been involved in the slave trade. My second was to do some research and find out more.

Like most people I had a rudimentary knowledge of the slave trade from history lessons at school and assumed that any black person in Britain at this time must automatically have been enslaved. Then I read Miranda Kaufman’s DPhil thesis ‘Africans in Britain: 1500-1640’ which gave me a whole new perspective. Dr. Miranda Kaufmann is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and carried out a detailed study using parochial records, wills, and a whole host of records familiar to family historians.

In a nutshell her thesis stated that there were at least 350 documented Africans in England during the Tudor and early Stuart period (1500 – 1640) who mostly came from North and West Africa. None were regarded as being enslaved by law.

How did these Africans get to Britain?

The Spanish and Portuguese had a thriving slave trade and many Africans ended up in Europe serving their Spanish and Portuguese masters. Royals, nobles, diplomats and merchants may have had African slaves who travelled around Europe with them. Some made it as far as Britain.

After the defeat of the Spanish Armada Queen Elizabeth I allowed English privateers to capture Spanish ships and their cargoes. If the cargo included African slaves they were usually freed on reaching England. There must have been a fair number of freed Africans as Elizabeth I issued an order for their transportation out of the realm but this was never enacted.

Jack Hawkins, one of the privateers, was England’s first slave trader. He started to trade in slaves from Guinea in 1562 and made four voyages before the Spanish decimated his ships and crew. That was the end of the slave trade in Britain until the 1640s. For most British merchants in the 16th and early 17th century Africa was viewed as a trading partner rather than a source of potential slaves. Fortunes could be made importing spices, hard woods, ivory and other commodities; and without overseas colonies there was no need for slaves. Some Africans were brought back to Britain to learn English to facilitate future trade.

Once in Britain Africans worked in a variety of jobs. Many were servants but working as a servant at this time was a respectable occupation. Some would have served as crew onboard merchant and navy ships. Some served as mercenaries in the army (Sir Pedro Negro served in Henry VIII’s army and was knighted in 1547.) Some were musicians (John Anthony of Stepney who was described as ‘Musician and Maurus’ in 1615. From the records that are available some appear to have had successful businesses (Stephen Driffield was a London needle maker).

The Africans intermarried and had children and appear to have been an accepted part of society. They are mentioned in wills and receive bequests from grateful employers, they also made bequests. William Offley’s will of 1600 stated “to ffrancis my black a moore I geve for her releife the some of tenne poundes and a gowne of twelve shillings the yarde“. (£10 was a huge sum, his other maids received 50 shillings.) Francis appears to have stayed in service to Lady Anne Bromley (formerly the wife of William Offley) and in 1625 she left a legacy of £10 to the poor of St Mary’s parish in Putney.

How did Chatherin end up in Barnstaple?

A search through the Barnstaple parish records shows that Chatherin was not the only black person in the town. Barnstaple is on the north coast of Devon and was a successful maritime trading town.

Perhaps Chatherin arrived on a seized Spanish or Portuguese ship which docked in Devon?

The earliest entry for a baptism of a black person in the Barnstaple Parish Register is 18 Jun 1565, the baptism of Anthony a ‘blackemore’ in the household of Mr Nicholas Witchalse. In 1570 Nicholas left his black servant 5 shillings “Item I geve unto Anthonye my negarre v s so that he remaine withe my wife otherwise yf she mynde not to kepe him to give hym v markes and lette hym go.”

Clearly Anthony is not enslaved but an employee who will be compensated with the amount of 5 marks if Mrs Witchalse does not keep him on after her husband’s death.

The next entry in the Barnstaple register is a baptism of Grace on 6 Apr 1596 ‘a Neiger’ in Richard Dodderidge’s house. There are at least half a dozen more entries in the next decade.

- 10 Apr 1598 Baptism of Elizabeth in Mrs Ayer’s house

- 22 May 1605 Baptism of Mary daughter of Elysabeth in Mrs Ayer’s house

- 26 Feb 1606 Baptism of Chatherin in Mr Lanyon’s house

- 10 Nov 1606 Baptism of Elysabeth daughter of Susanna ‘a nygor’ – they appear to be independent of any household

- 8 Jul 1605 Burial of Mary daughter of ‘Elysabeth a negro servante to Mrs Ayer’

- 12 Dec 1607 Burial of Susanna – ‘ye childe of a negor’

We don’t know what happened to Chatherin. William Lanyon died in 1614, if he left a will it has been lost so we have no clues about his family or Chatherin. There are a couple of mentions of a ‘Katherine’ in other parish registers in that part of England and its tempting to think they could be her but that is pure speculation on my part.

- 4 Jan 1612 Christ Church Bristol – Burial of Katherine a ‘blacke negra’ she was ‘a servant at the horshed’ – this was the Horshed Tavern in Christmas Street

- 31 Jan 1635 St Andrew’s Plymouth – Baptism of Margery, daughter of Katherine a ‘blackmoore’ and Fredericke Daniel

If you want to find out more on this subject I recommend: