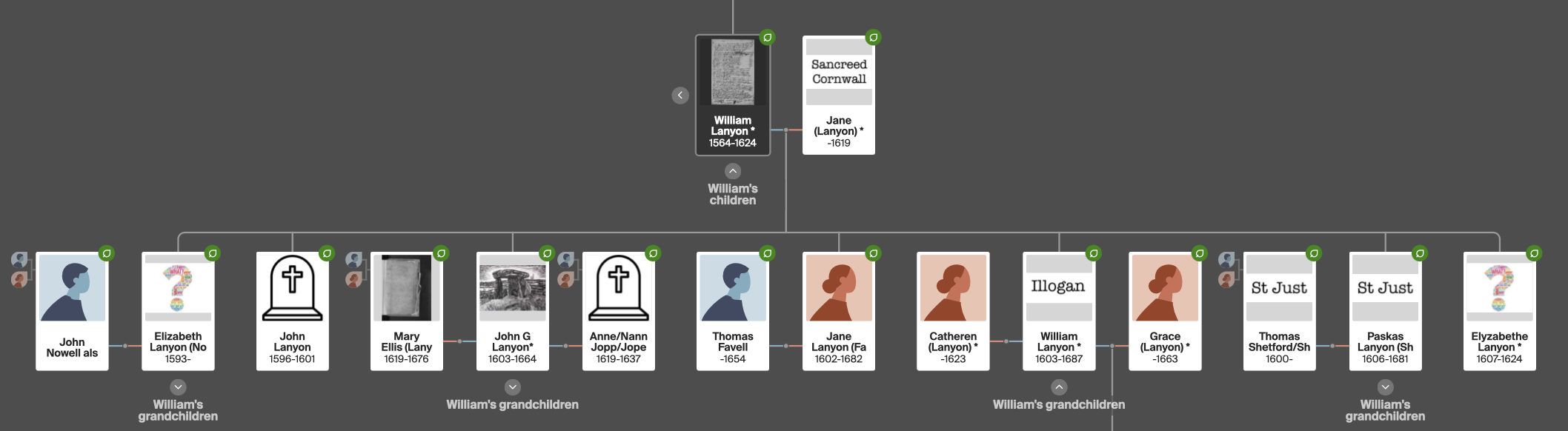

William was the son of William Lanyon and the grandson of John Lanyon Esq.

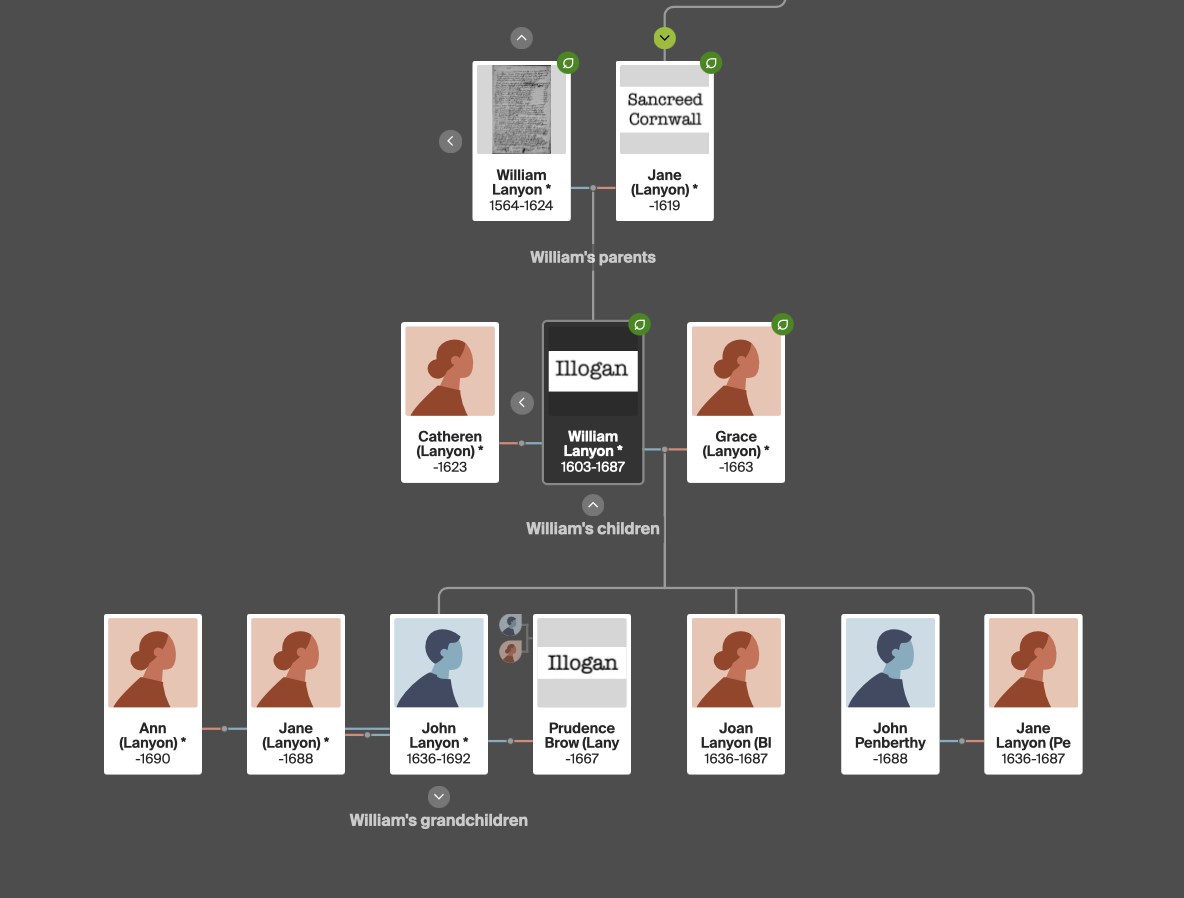

William was baptised at Sancreed in 1603. He may have had a first wife called Catheren as there was a Catheren Lanyne buried at Illogan in 1623. He married Grace (surname not recorded) at Illogan in 1636. He signed the Protestation Return on 1641/2 as William Lanyne Illogan.

William had three children who’s baptisms and burials have not been traced. Assumption is that they were all born after their parent’s marriage in 1636 and were still alive when their father’s will was proved in 1687.

- John aft.1636-aft.1687 married Jane

- Jane aft.1636-aft.1687 married John Penberthy – children

- Joan aft.1636-aft.1687 married Bloyes, no children at the time of the will.

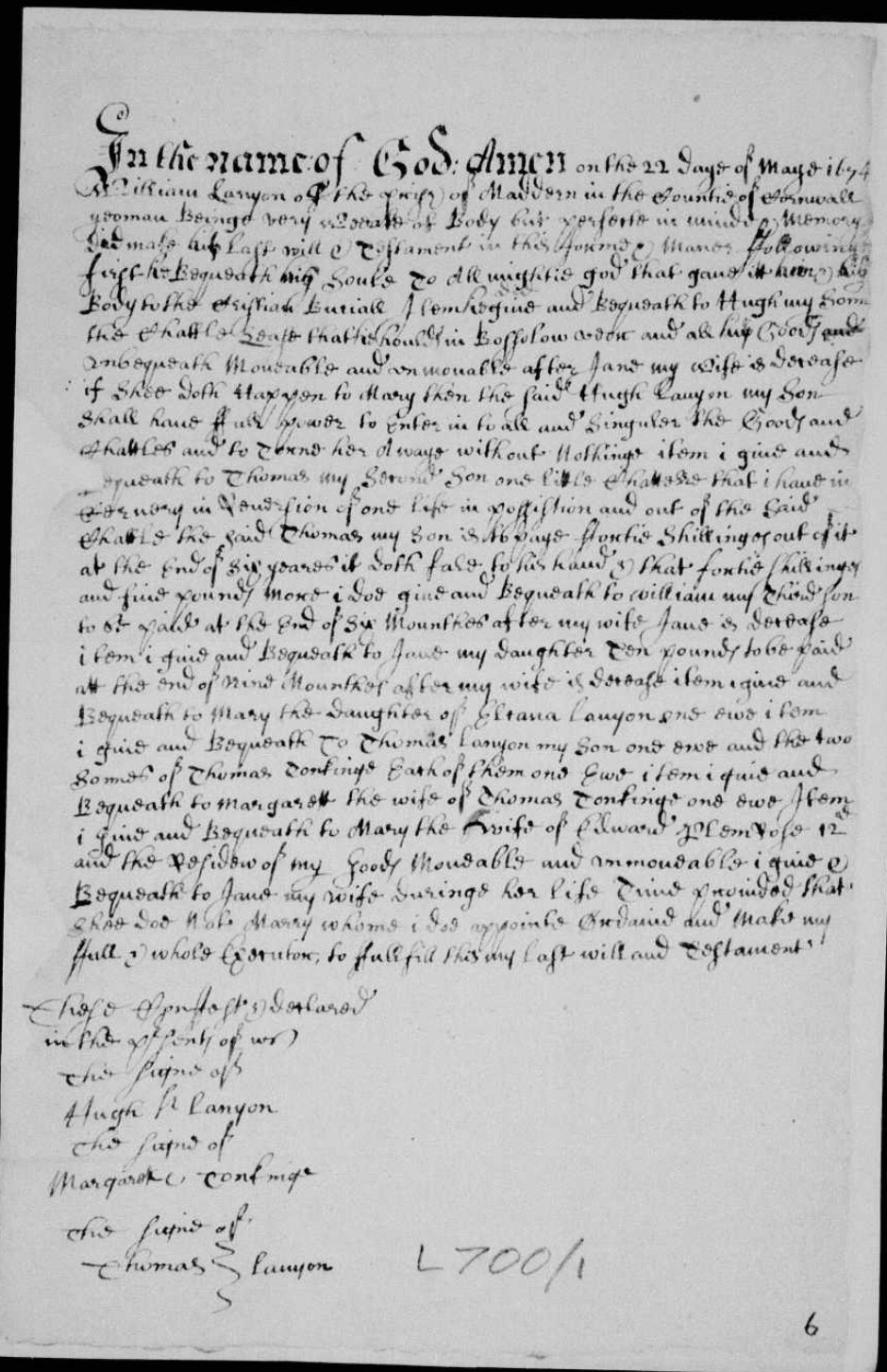

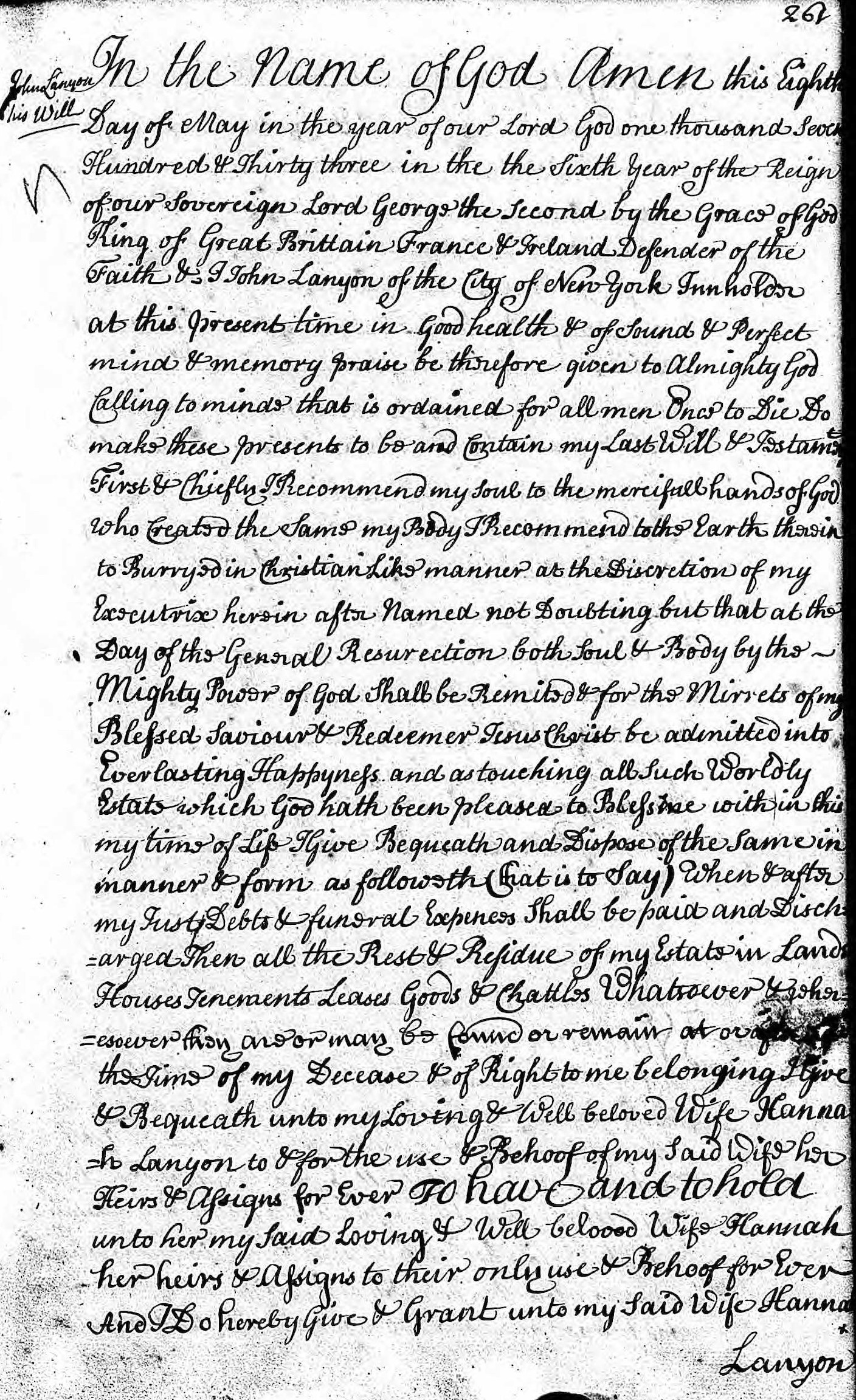

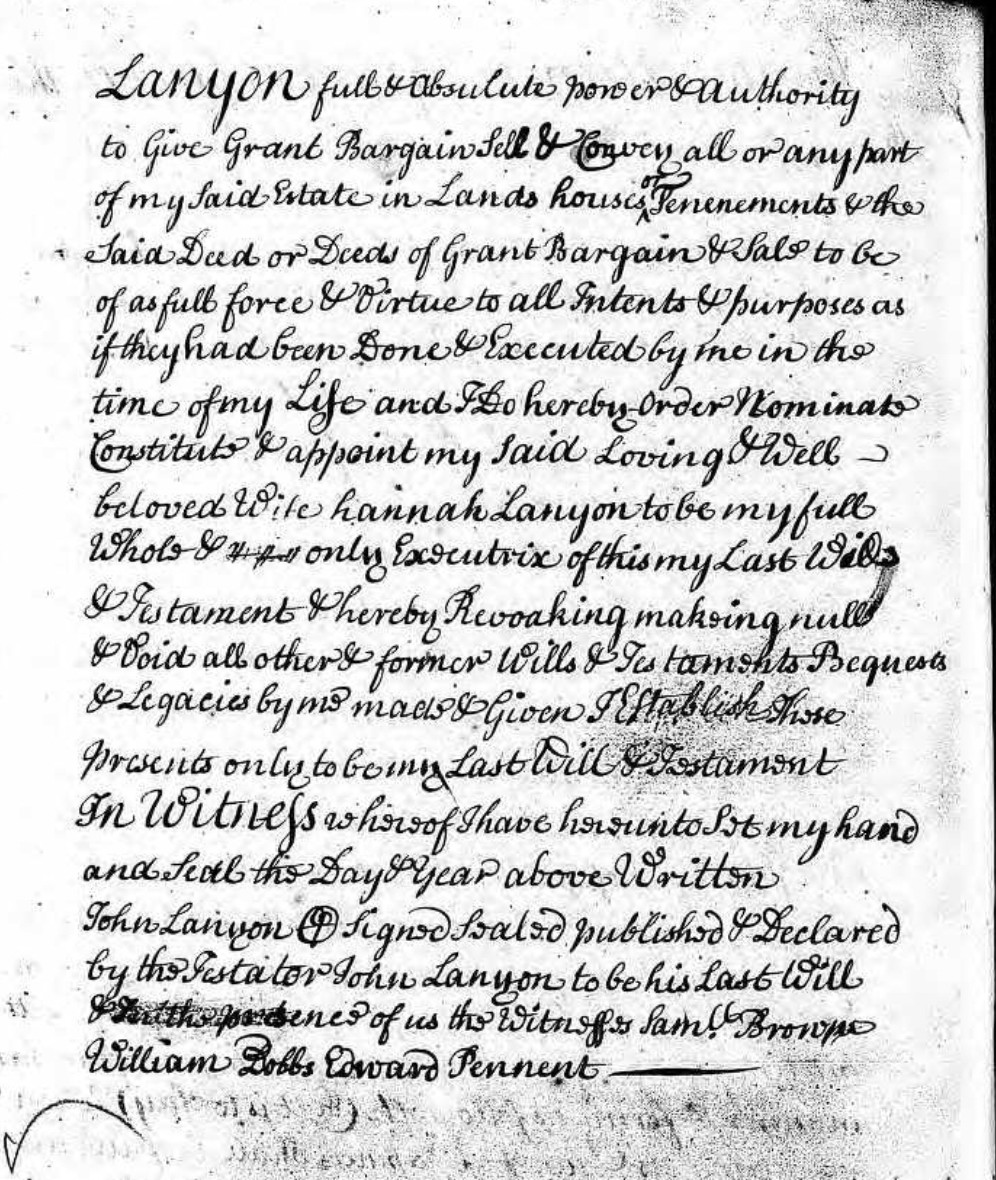

William’s will is long, I’ve only added the first page, and a transcript.

William’s son John Lanyon was married at least twice. His first wife was Prudence Brow and they married at Illogan in 1663. They had a daughter Grace baptised in 1665 and Prudence died in 1667. John married again to Jane, surname unknown. John had three more children but it isn’t clear if the mother was Jane or Prudence as we don’t know the dates of baptism just the dates of their burials:

- William – 9 Jul 1669

- Elizabeth – 27 Jun 1669

- Thomas – 13 Jul 1669

It appears as though William, Elizabeth and Thomas died in an epidemic – they were buried within three weeks of one another.

There is a John Lanyon who married Ann at Illogan in 1690. Perhaps Jane died after the will and John remarried. No record of any children.

Grace baptised in 1665 married Stephen Cock at Illogan in 1683 and is mentioned in her grandfather’s will. It sounds as though she has had a child and perhaps lost it. ‘If my granddaur Grace Cock have another child in my lifetime £100 to same at 21.’

The John Lanyon of St Ives ‘my kinsman’ mentioned in William’s will is his nephew, the son of John Lanyon and Mary Ellis. William is also mentioned in Mary (Ellis) Lanyon’s will of 1676.

We don’t know much about William of Illogan but we do know he was summoned to appear at the Consistery Court of the 29 April 1663. We don’t know what the summons was for but on the 16 May he “makes humble acknowledgement of his sorrow for not appearing.” Source – letter from HL Douch, curator Royal Institution of Cornwall to WSL Lamparter. 1 Nov 1962.

With no surviving grandchildren called Lanyon this little branch of the family died out.